The subject of water on Mars has been a topic of scientific debate and speculation for well over 100 years. Since the earliest reliable observations of Mars via telescope, it had been thought that water ice and water vapour existed on the planet and in its atmosphere as a result of the seeing the polar ice caps (although we now know the major stakeholder in these is carbon dioxide) and cloud formations.

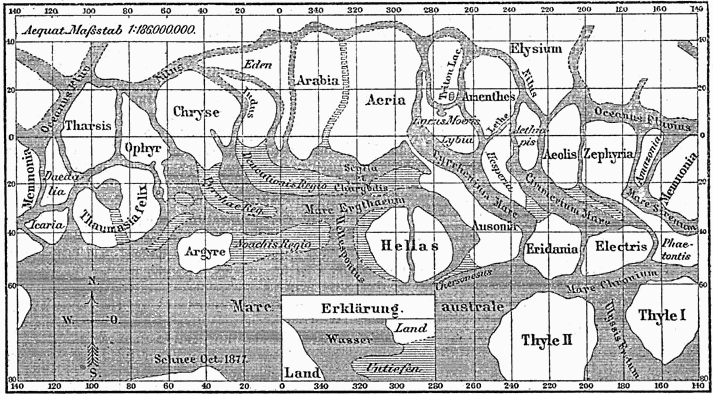

However, the idea that Mars was still subject to liquid water flowing across its surface in our modern era became popularised in the late 1800s. In 1877, respective Italian Astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli – already noted for his observations of Mars in which he correctly identified and named multiple visible surface features – used the Great Opposition of 1877 (when Mars and Earth were both on the same side of the Sun relative to one another and Earth was effectively “overtaking” Mars in their respective orbits, thus bringing the two into “close” proximity to one another) to carry out further observations. During these he noted the presence of multiple canali on Mars.

Canali is an innocent term, meaning “channel”, and Schiaparelli simply used this term to differentiate what he thought is saw from other features he observed. But in English-speaking newspapers it was later translated as canals, evocative of artificial and intelligent construction. This resulted in wealthy Bostonian businessman Percival Lowell, following his return to the United States in the early 1890s to establish an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, specifically (initially at least) so he could observe these “canals” for himself.

Over the course of 15 years (1893-1908), Lowell saw his canals, which grew into a globe-spanning network and led to the publication of three books (Mars (1895), Mars and Its Canals (1906), and Mars As the Abode of Life (1908 – an original copy of which I actually own!) in which he expounded his theory that Mars had a network of canals built by an ancient civilisation in a last-ditch effort to carry liquid water from the planet’s poles to their equatorial and temperature cities as the planet increasingly became more desert-like.

Lowell stuck to this belief throughout his observations in spite of increasing scientific evidence that Mars was likely incapable of supporting liquid water on its surface and observations from other observatories with larger telescopes than his which could not find any evidence of “canals”, and that at least some of what he was seeing was actually (as Schiaparelli had believed) lines of demarcation between different elevations / terrains.

As a result of this belief, Lowell has become regarded as a bit of a crackpot – which is a same, as he led a remarkable life with multiple achievements as a traveller, diplomat, writer and armchair scientist, and did gain recognition in his lifetime for his work – He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1892 and then to the American Philosophical Society in 1897, whilst the volume of work he carried out as an astronomer outside of his theories about Mars saw him receive the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société Astronomique de France, in 1904.

This volume of work include daytime studies of Venus and the search for “planet X”, a planetary body believed (and still believed by some) to be orbiting the Sun far out beyond the orbit of Neptune. In fact, the Lowell Observatory became a centre for this work, for which it was rewarded in 1930 when Clyde Tombaugh located Pluto using the observatory’s telescopes and equipment.

Of course, whilst liquid water does not exist on the surface of Mars today and hasn’t for billions of years, we have found plenty of evidence for its past presence on the planet’s surface.

In my previous Space Sunday article, for example, I wrote about the Great Lake of Mars, Lake Eridania, whilst both the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity and Mars 2020 rover Perseverance have literally been following the evidence for free flowing water in both of the locations on Mars they are exploring. Prior to them, the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity both uncovered evidence of past liquid water on Mars, as have orbital vehicles from NASA, Europe and other nations. But the two big questions have always been – where did it go, and where did it come from?

In terms of where it went, the most common theories are that the water either evaporated and was lost to space along with Mars’ vanishing atmosphere relatively early in the planet’s life or retreated down into the Martian crust where it froze out into icy “reservoirs”. The first is likely for a certain volume of water, whilst subterranean tracts of water ice have been located not too far under the surface of Mars. However, the latter cannot possibly account for the amount of water believed to have existed on the surface of Mars in its early history, not could simple evaporation account for the disappearance of to greater majority of it. So where did the rest go? And where did it come from originally?

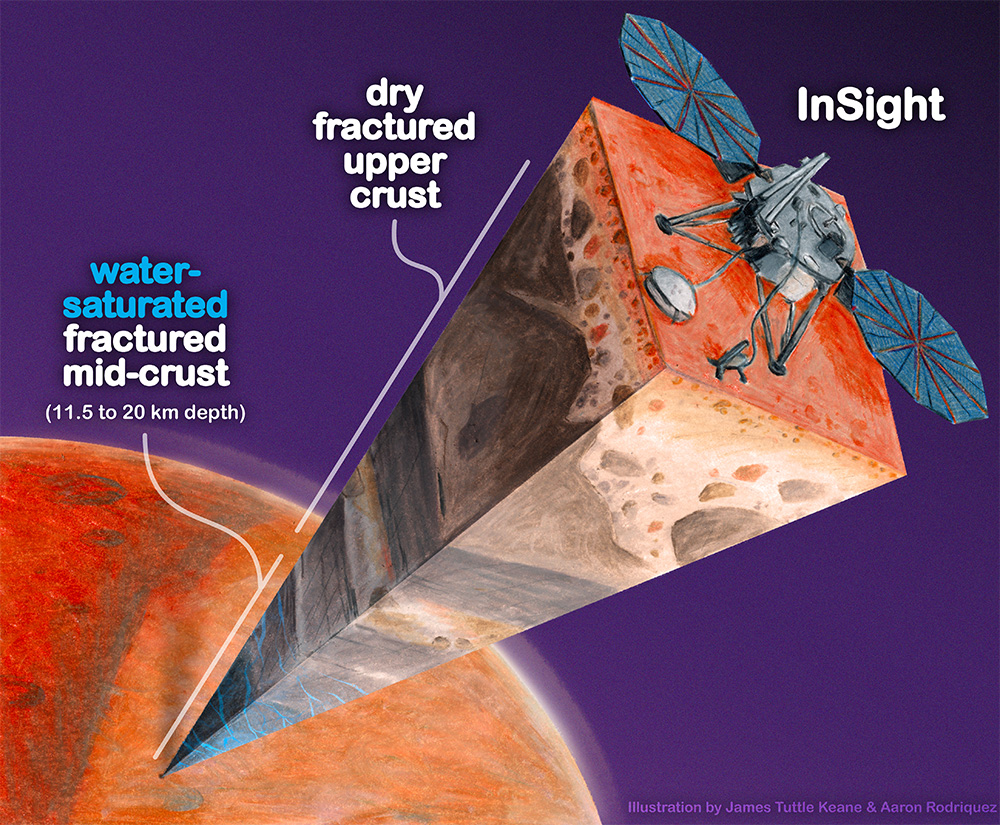

Well, in a new report published this month a team of scientists believe they have the answer, and it lay within data obtained by NASA’s InSight (INterior exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) lander.

This ambitious craft landed on Mars in 2018, with the mission running from November of that year through until the end of December 2022. In particular, the lander carried with it two unique instruments it deployed onto the Martian surface using a robot arm. One of these was the French-lead Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS), designed to measure marsquakes and other internal activity on Mars and things like the response to meteorite impacts, in order to better understand the planet’s internal structure. The data continues to be studied, and has revealed much about the planet’s internal structure and its history.

Most recently, a US team from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego and the University of California, Berkeley, have been reviewing the SEIS findings specifically to try to answer the question of where the water went. In particular, they have been using mathematical models employed here on Earth to locate aquifers and oil and gas fields deep underground. By adjusting the models so they provided results consistent what is largely known about the Martian crust down to a depth of several kilometres below the surface, they ran a series of passes on data gathered from deeper and deep within the planet’s crust, In particular, the came across two interesting results. The first indicated that while deposits of water ice do exist below the surface of Mars, and less than 5 km from the surface, they are likely to be far less commonplace than had been thought. The second result they took note of was consistent with those indicative of layers of water-saturated igneous rock deep within the Earth’s crust.

Most interestingly, the results of the SEIS data modelled suggest this deep layer of rock and water – laying some 11.5 to 20 km below the surface of Mars could be widespread across the planet to the extent that it could contain more water than would have been required to fill the oceans and seas of ancient Mars.

Taken together, these result indicate that while the theories about water on Mars being lost to space or frozen into subsurface ice are still valid, the vast majority of the water most likely retreated deep down into the planet, possibly returning to the reserves from which it might have originally burst forth to flood parts of Mars during the planet’s late Noachain / early Hesperian period of extreme volcanic activity.

One intriguing question that arises from this work is related to the potential for Mars to have harboured life, and what happened to it as the water vanished. if the modelling in the study is correct, and the water did retreat deep under the surface of Mars and form aquifers and pools with the rocks there, did any ancient microbial life gone with it, and if so – might it have survived? The pressure and temperatures at the depth which the water appears to reside would keep it both liquid and warm and provide energy, as would mineral deposited within the rock; so the question is not without merit.

Establishing that there is a big reservoir of liquid water provides some window into what the climate was like or could be like. And water is necessary for life as we know it. I don’t see why [the underground reservoir] is not a habitable environment. It’s certainly true on Earth — deep, deep mines host life, the bottom of the ocean hosts life. We haven’t found any evidence for life on Mars, but at least we have identified a place that should, in principle, be able to sustain life.

– Michael Manga, Professor of Earth and Planetary Science, UC Berkeley

But the is a question that’s unlikely be to answered any time soon. Determining if the environment is at the very least amenable to life, much less actually finding evidence for life within it – or even simply reaching any of the water deposits –is going to be pretty much impossible for a good while yet. Current deep drilling techniques here on Earth for extracting oil and gas only go down to around 2 km; getting that sort of equipment to Mars and enabling it to dill down at least 11-12 km will pretty much remain the stuff of dreams for a good while to come.

JUICE to Swing by the Moon and Earth

The European Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission will be making a first-of-its kind fly-by of the Moon and Earth this week, the first in more than 5 gravity assist manoeuvres the vehicle will make (excluding those made while orbiting Jupiter) during its mission to study the icy moons on the Jovian system.

Such manoeuvres are often used with space missions and for a variety of reasons. With JUICE, it means the craft could be flown into space using a medium-lift launch vehicle and make (and albeit relatively sedate) flight to Jupiter, involving a total of three fly-bys of Earth and one of Venus to accelerate it to a peak velocity of 2.7 km per second using the minimum of fuel and then slingshot it out to a point in space where it will intercept the Jovian system, and they use further flybys of the planet and its Moons to both slow itself down into orbit around them and then adjust its course so it can study the icy moons of Jupiter – Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa.

This first fly-by comes 16 months since the launch of the vehicle, and will be the very first Earth gravity assist which also employs the Moon as a critical component. On August 19th, Juice will as around the Moon at a distance of just 700 km (reaching the altitude at 21:16 UTC), using the Moon’s gravity to swung it onto a trajectory that will see it pass by Earth just over 24 hours later, passing over north-eastern Asia and the Pacific at an altitude of just 6,807 km on the morning of August 20th (local time) before heading back out to loop around the Sun. After this it will get a further gravity assist from Venus in August 2025 and then two more from Earth (without the Moon helping) in 2026 and 2029, that latter of which will slingshot the vehicle on it way to rendezvous with Jupiter and its moons.

On August 15th, Juice briefly caused a stir when it was mistaken as a near-Earth object (NEO) on a potential collision course with Earth. At 27 metres across, most of which is some 85 square metres of solar arrays, Juice is a strong reflector of sunlight, and this briefly confused systems at the ATLAS Sky Survey, Hawai’i, which attempts to locate, identify and track potentially threatening NEOs. However, the system’s confusion was quickly identified as actually being the Juice spacecraft and the alert corrected.

This was actually the second time an ESA deep-space vehicle has been mistaken as a hazardous NEO; in November 2007, and as it approached Earth for a flyby, Europe’s Rosettta mission spacecraft – also with a large span of solar arrays – was also briefly mis-identified as a NEO on a possible collision course with Earth. On that occasion, it was mis-identified by a human observer, and further manual checking was required before it was confirmed the object being tracked was actually the Rosetta spacecraft and not of any threat to Earth.

Following its arrival at the Jovian system, Juice will spend 1259 days orbiting the system, the majority of which will be in Jupiter-centric orbits that will allow it to study Ganymede, Callisto and Europa, with numerous gravity-assists of both Ganymede and Callisto used to alter its trajectory and velocity, allowing it to study them from different orbital inclinations and also to dip down into the inner Jovian system to study Europa.

However, the final 284 days of the time (from early 2035) will be spent in a dedicated orbit around Ganymede, allowing the spacecraft to complete some 6 months of dedicated studies of the moon once it has settled into a 500 km circular orbit around Ganymede. By the end of 2035, the spacecraft is expected to have expended the last of its 3 tonnes of manoeuvring propellants, bringing the mission to an end. without the ability to manoeuvre, Juice is expected to quickly fall victim to further Jupiter gravitational perturbations and crash into Ganymede within weeks of running out of propellants.