Monday April 8th 2024 marks 2024 only total solar eclipse of the year (and only one of two which might be witnessed during the year the other being an annular eclipse on October 2nd, 2024), with North America being treated to the spectacle.

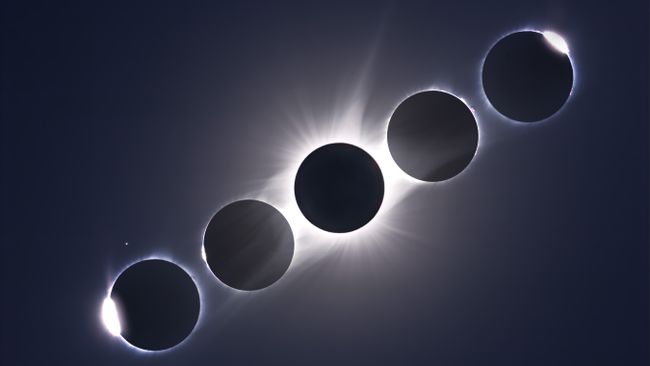

A total eclipse is when the Moon crosses directly between Earth and the Sun in a manner which means it completely blocks the face of the Sun from view to those directly “under” the Moon’s path across the sky. This is the region known as the path of totality, marked by the Moon’s shadow marching its way across the face of the Earth as the Moon passes between planet and star. Within that path, the full light of the Sun is blocked for a brief period, plunging the land into twilight before the face of the Sun re-emerges from the limb of the Moon as the latter continued on in its orbit.

As I’ve mentioned before in these pages, a total solar eclipse is the most intense and fascinating of the various types of eclipse that can be observed from Earth, and they tend to occur roughly every 12-24 months, affecting different parts of the world depending on factors such as the Earth’s rotation at the time, the position of both the Sun and Moon relative to Earth, etc. Thus, not every total eclipse is necessarily so easily visible; the path of totality can often be in very remote places or over sparsely populated regions or even far out at sea.

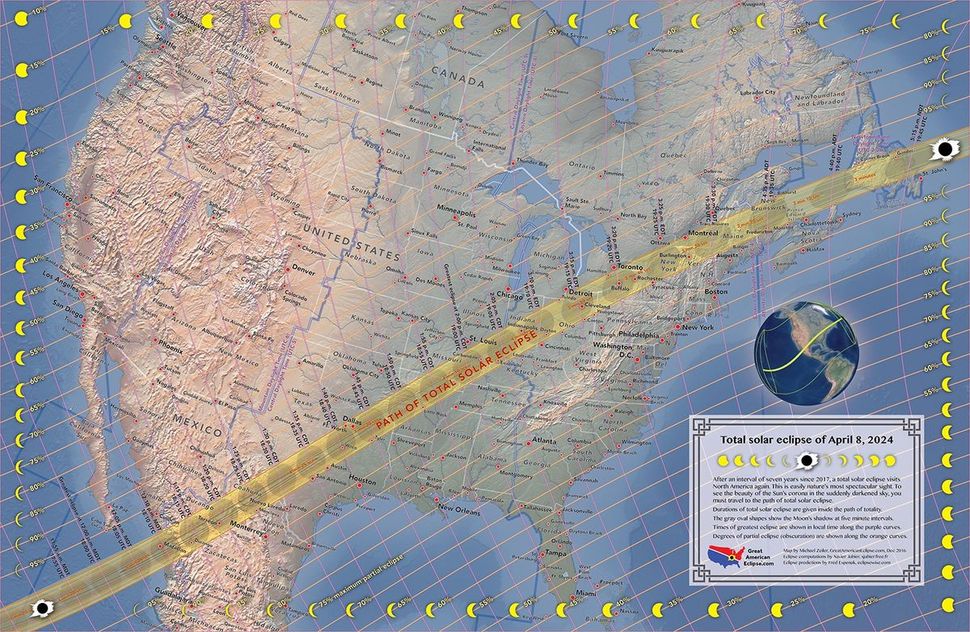

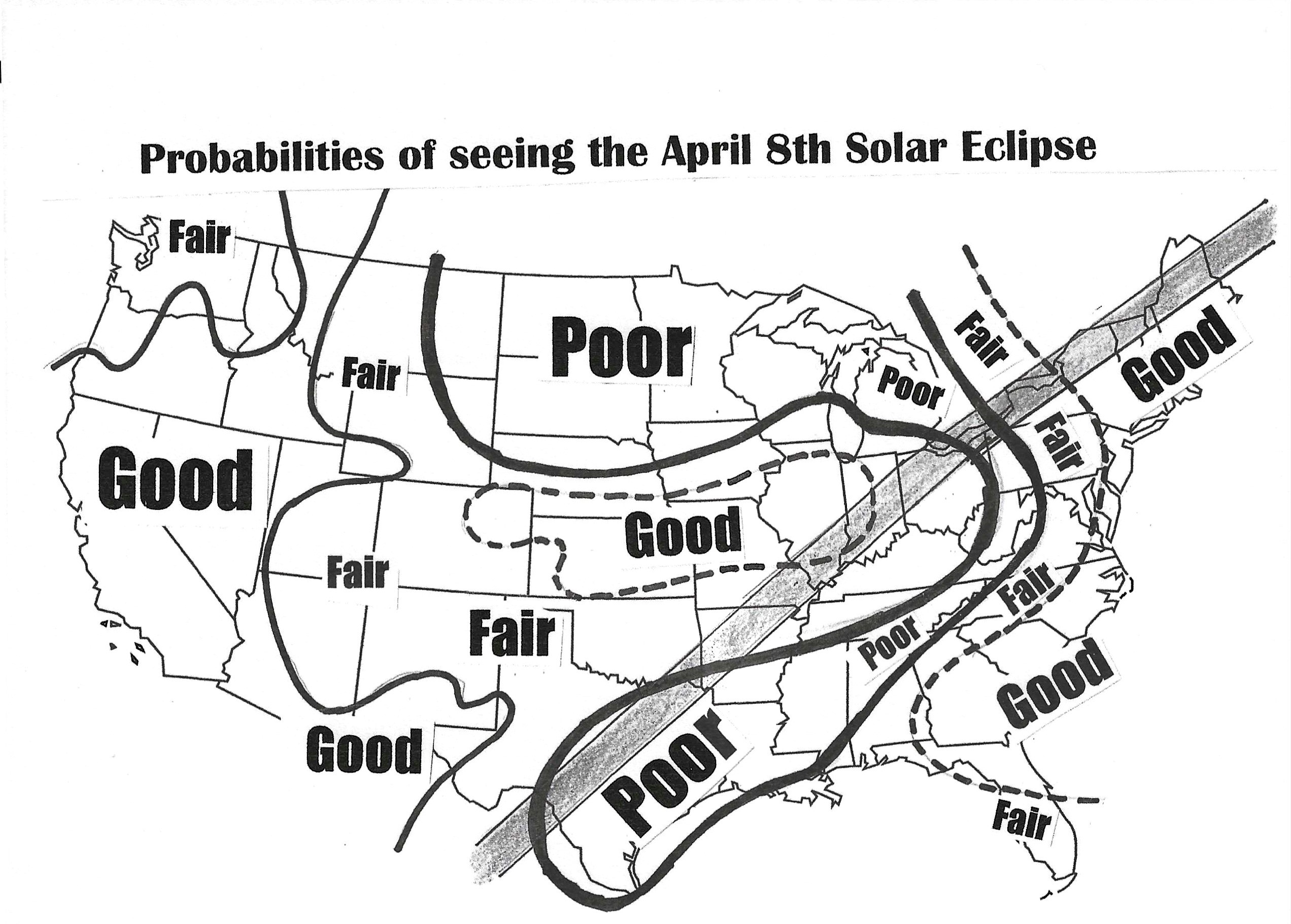

The event on April 8th 2024, however, is a little different. The 184-km wide path of totality will extend across 15 US states, whilst its ground track across North America will include Sinaloa, Durango and Coahuila in Mexico and Ontario, Quebec (where it will brush both Toronto and Montreal respectively), New Brunswick and sweep over the Labrador coast of Newfoundland close to St. Johns. This means it will be potentially visible (weather permitting) to around 32 million people in the US alone. What’s more, and in a rarity for total eclipses, it comes just seven years after the last total eclipse was visible from the continental United States (prior to that, the previous one to occur over the contiguous US was in 1979, and the next will not be until 2044).

If you are lucky enough to lie along the path of totality, and the weather is suitable for you to view it, please keep in mind these common sense guidelines:

- Never look directly at the Sun – even with sunglasses or by using dark material such as a bin bag or photo negative; these filters do not protect your eyes against infrared radiation and can cause permanent eye damage.

- Only look at the sun if you have certified eclipse glasses and are wearing them.

- Only use a telescope or binoculars to project an image of the Sun onto white card, and never use either instrument to observe the Sun directly unless you have a certified solar filter fitted.

The best way to view an eclipse if you do not have eclipse glasses or have a telescope or binoculars to project the Sun’s image onto card, is via a pinhole camera:

- Cut a hole in a piece of card.

- Tape a piece of foil over the hole.

- Poke a hole in the foil with a pin.

- Place a second piece of card on the ground.

- Hold the card with the foil above the piece of card on the floor to project an image of the Sun onto it, and look at the image. Do not use the pinhole to look directly at the Sun.

There are a number of terms common to eclipses which are worth mentioning for those who wish to follow the event, but are unfamiliar with the terminology. Specifically for a total eclipse these are:

- The umbra, within which the object in this case, the Moon) completely covers the light source (in this case, the Sun’s photosphere).

- The penumbra, within which the object is only partially in front of the light source.

- Photosphere, the shiny layer of gas you see when you look at the sun.

- Chromosphere, a reddish gaseous layer immediately above the photosphere of the sun that will peak out during the eclipse.

- Corona, the light streams that surround the sun.

- First contact, the time when an eclipse starts.

- Second contact, the time when the total eclipse starts.

- Third contact, the time when the total eclipse ends.

- Fourth contact, the time at which the eclipse ends.

- Bailey’s beads, the shimmering of bright specks seen immediately before the moon is about to block the sun.

- Diamond ring, the last bit of sunlight you see right before totality. It looks like one bright spot (the diamond) and the corona (the ring).

As noted, a total eclipse occurs when the observer is within the path of totality marked by the Moon’s shadow – which is formally called the umbra – passing along the surface of the Earth. For those in Mexico, much of the USA and Canada outside of the umbra, there is still the opportunity to see a partial solar eclipse if you are located within the penumbra.

If you are observing the eclipse (particularly along the line of totality), you might keep an eye out for some / all of the following:

- If you look at the ground around you just before totality occurs and the Moon completely covers the disk of the Sun; you might see the phenomenon of fast-moving shadows, called shadow bands, racing across the ground under your feet. These might also occur as the Sun starts to re-emerge from behind the Moon.

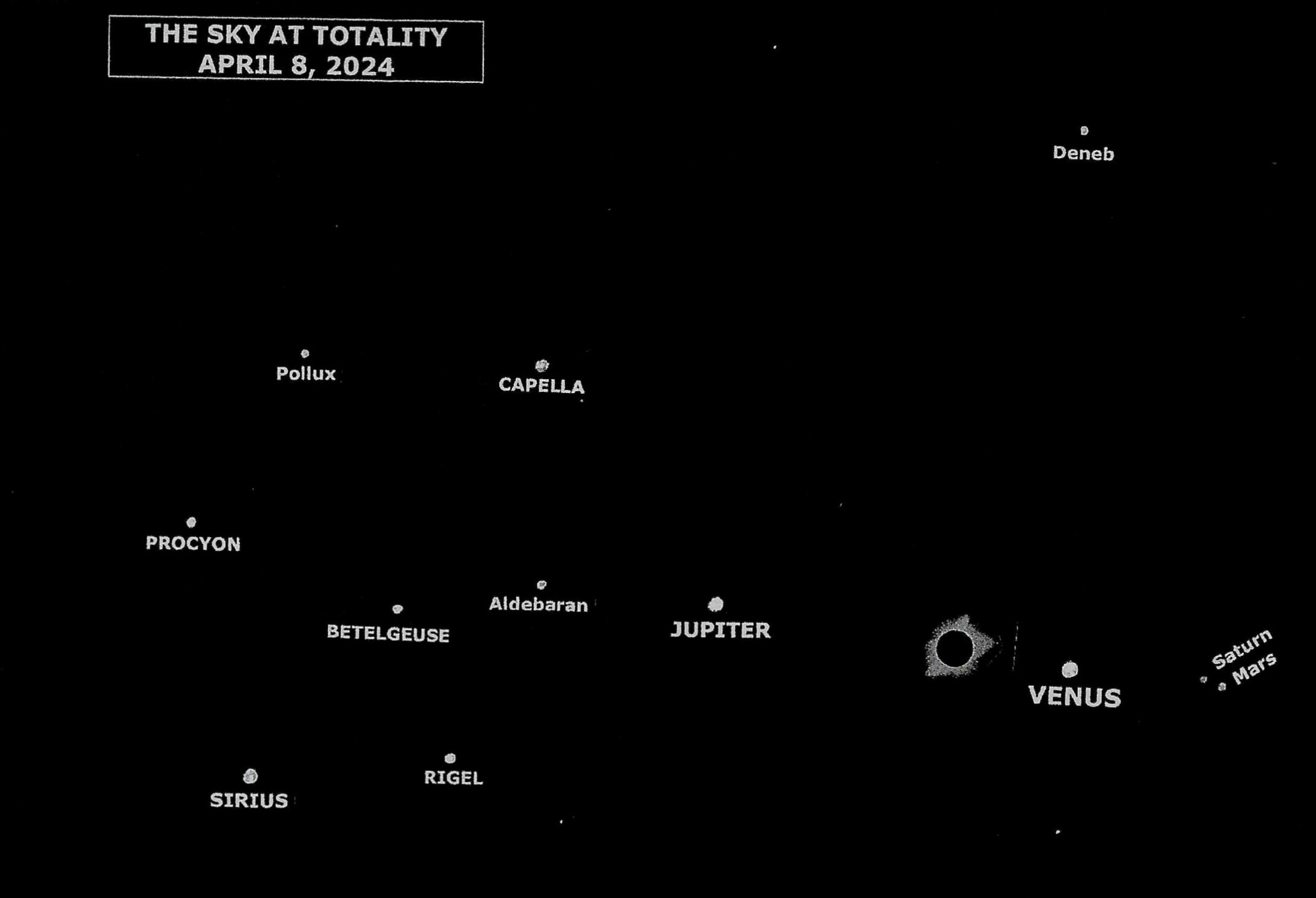

- During totality, keep an eye out for the brighter stars becoming visible during totality, together with the following planets:

- Jupiter: roughly 30o above and to the left of the Sun / Moon.

- Venus roughly 15o below and to the right of the Sun / Moon.

- Saturn and Mars (both very faint) roughly 20o below Venus, close to the horizon and further to the right.

- The very keen eyed might also be able to spot comet 12P/Pons-Brooks as a fuzzy dot just off to the right of Jupiter (although you will need to be very keen-eyed!

- Watch and listen to the local animals and wildlife (if present). Birds may stop singing, with some flying to their roosts, cattle might behave is if it is evening , etc., as they become confused by the local twilight.

- During the solar eclipse, you may see colours shifting, giving familiar objects unusual hues. This natural shift in colour perception is caused by fluctuating light levels resulting from the darkening of the sun.

If you prefer not to watch the eclipse directly, or are not lucky enough to live along the path of totality (is the weather is pooping on you seeing it if you are), then it can be followed on-line at the following resources:

- Via a NASA livestream.

- Via the Timaanddate livestream.

- Via the University of Maine’s balloon livestream from the stratosphere.

- Via the McDonald Observatory livestream.

Totality Times (UTC) for Notable North American Locations

- Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico – 18:07; duration: 4 minutes 20 seconds.

- Durango, Durango, Mexico – 18:18; duration: 3 minutes 50 seconds.

- Piedras Negras, Coahuila, Mexico/Eagle Pass, Texas, U.S – 18:27; duration: 4 minutes, 24 seconds.

- Dallas, Texas – 18:40; duration: 3 minutes 52 seconds.

- Indianapolis, Indiana – 19:06; duration: 3 minutes, 51 seconds.

- Cleveland, Ohio – 19:13; duration: 3 minutes, 50 seconds.

- Erie, Pennsylvania – 19:16; duration: 3 minutes, 43 seconds.

- Rochester, New York – 19:20; duration: 3 minutes, 40 seconds.

- Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada – 19:18; duration: 3 minutes, 31 seconds.

- Montreal, Quebec, Canada – 19:26; duration: minutes 57 seconds.

- Tignish, Prince Edward Island, Canada – 19:35; duration: 3 minutes, 12 seconds.

- Catalina, Newfoundland, Canada – 19:43; duration: 2 minute, 53 seconds.

Note that part of north Europe – notably the UK – will be able to witness a partial solar eclipse.

Witness a Recurring Nova

At some point between now and September, those of us in the northern hemisphere will have the opportunity to witness an astronomical phenomenon called a recurring nova. During the event, a star normally invisible to the naked eye will suddenly flare up in brilliance, from around magnitude 10 to magnitude 2 (roughly as bright as Polaris, the Pole Star, in Ursa Minor within the northern hemisphere), and will remain that way for perhaps a day, before dimming back down again over about the course of a week, vanishing once more from naked-eye visibility.

This phenomenon occurs about once every 80 years, and has been observed in the night sky since at least 1217, although it was only officially recognised as a recurrent nova in 1866. It is linked to an interesting binary start system called T Coronae Borealis (T CrB), comprising a very large (and comparatively cool) red giant star, surrounded by a dense cloud of material it is constantly giving off. Within that material lies a much smaller and hotter white dwarf star, the two orbiting about a common centre once every 228 terrestrial days.

For most of the time, the red giant is the dominate partner in this binary relationship, giving out the most visible light as a M3 giant. However, as the white dwarf orbits the red giant, it accumulates matter and mass from the dense gaseous cloud surrounding the red giant, acquiring around the mass of Earth over a period of 50 terrestrial years. As it continues to gather more mass from the red giant, the pressure and temperature of material on the white dwarf’s surface increase. This results in three things happening.

The first is that the pressure within the white dwarf starts to rise as it undergoes increasing compression. At the same time, its temperature rises, causing it to brighten, increasing the overall brightness of the two stars. This occurs over a period of around 8-10 years, when the brightness of the two stars also starts to fluctuate as the white dwarf reaches a point where it starts pulling in mass directly from its companion.

At this point, things start to happen comparatively rapidly. The pressure contraction of the white dwarf accelerates, the brightness of the two stars dims as it pull more material from the red giant – and the temperature within the outer layers of the white dwarf reach the point of hydrogen ignition, and they go off like a star-sized H-bomb, the explosion ripping millions of tonnes of matter from the white dwarf and causing its brightness to rapidly increase to the point where the system becomes visible to the naked eye on Earth.

Following the explosion, the material ejected by the white dwarf is lost to space, its own pressure and temperature dramatically fall, the light from the explosion dims – and the process stars all over again, reaching a peak once more some 80 years later.

Or at least, that’s the theory; as T CrB has only been officially observed as a recurring nova twice (1866 and 1946), astronomers are working on limited data. As such, there is some uncertainty about things. However, the observations made of T CrB since 2015 do closely match those observed in the run-up to the 1946 outburst, including the fact that after a period of 8 years of fluctuating brightness, T CrB started dimming in April / May 2023, suggesting the white dwarf is again on the brink of going nova.

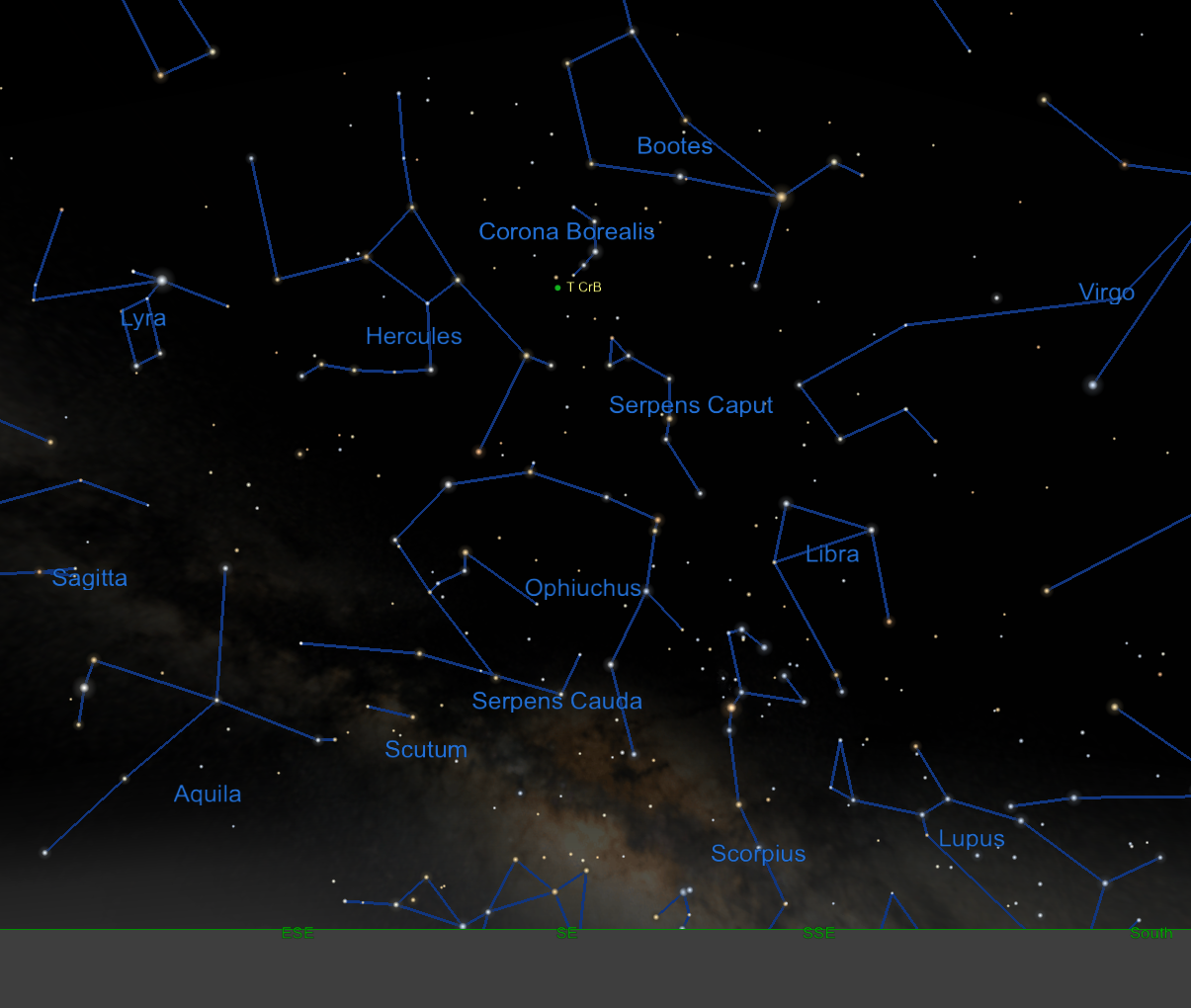

To find T CrB, look for Corona Borealis the Northern Crown, a curved constellation just west of Hercules, best seen in the Northern Hemisphere. The crown’s brightest star is Alpha (α) CrB, at magnitude 2.2 — about as bright as T CrB will appear in outburst. From there, look east down the crown’s curve, passing the stars Gamma (γ) and Delta (δ) CrB. The soon-to-be showstopper, T CrB, is about 2.2° east of Delta. While at the time of writing not visible to the naked eye, T CrB can be seen with a modest telescope or binoculars.