We’re probably all familiar with the concept of some Moons within our solar system – notably Saturn’s Enceladus, and Jupiter’s Europa, Ganymede and Callisto – potentially being completely encompassed by a liquid water (or at least a slushy) ocean under their surfaces. But how about a moon being almost completely encompassed by an ocean of hot volcanic magma just a few kilometres under its surface?

That’s the proposal contained within a new paper written under the auspices of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and based on an analysis of data obtained by the Jovial Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument aboard NASA’s Juno mission in reference to Io, the innermost of the four Galilean moons of Jupiter.

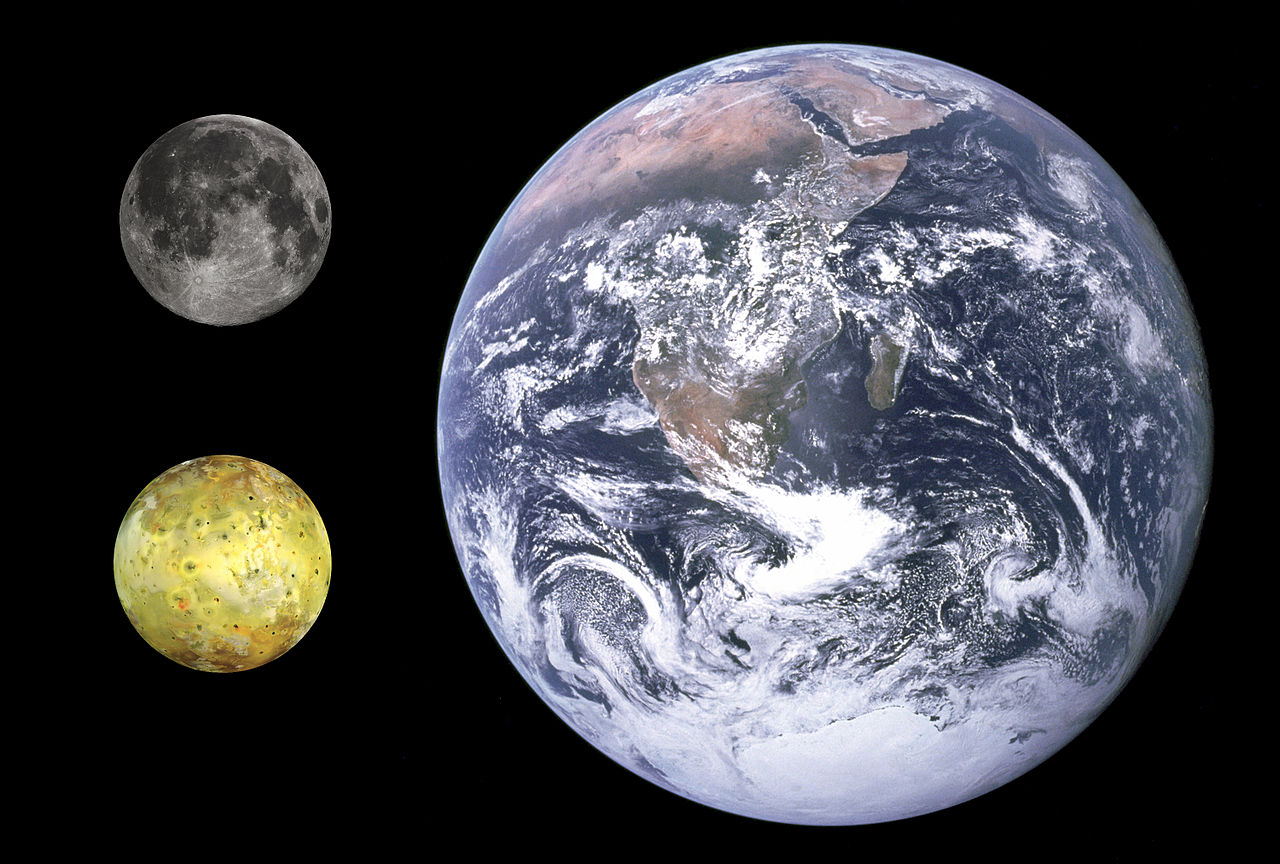

Of course, we’ve long known that Io, a moon slightly larger than our own, is the most volcanic place in the solar system. More than 400 active volcanoes have been identified since we first witnessed one erupting in 1979, courtesy of NASA’s by Voyager 1 in 1979, and the Juno mission has imaged no fewer than 266 actively erupting during its periodic fly-bys of Io as it studies Jupiter and its moons. The overall driving force behind these volcanoes is tidal flexing deep within Io’s core and mantle, the results of the moon being in a constant state of flux thanks to the gravitational influences of (most particularly) Jupiter to one side and the three other Galilean satellites on the other.

However, there has always been something of a question as to how these volcanoes might – or might not – be related and directly powered. Here on Earth, volcanism usually occurs as a result of decompression melting within the asthenosphere – the upper limits of the mantle directly under the lithosphere/crust comprising solid and partially-melted rock. This gives rise to magma, which is then forced upwards through the lithosphere as localised volcanic eruptions. This was long held to be the case with Io, with scientists believing its volcanoes, like the majority on Earth, were driven by the upwelling of individual magma flows.

But during the Galileo spacecraft’s observations of Io between 1995 and 2003, the data gave tantalising hints that Io’s volcanism could be the result of a somewhat different process, but it has taken the unique capabilities of the Juno spacecraft to confirm this to be the case. By gathering extensive thermal and infrared imaging of Io’s mantle, the JIRAM instrument has been able to put together a comprehensive view of the upper layers of Io’s mantle, revealing that far from being a layer mix of solid and partially melted rock, Io’s asthenospheric region is entirely molten in nature.

In other words, lying just below Io’s lithosphere (roughly 12-40 km thick) is a moon-girdling ocean of magma, some 50 km thick, with a mean temperature of some 1,200ºC, and which powers all of Io’s active volcanoes.

This may not sound exciting in the scheme of things, but it further demonstrates the uniqueness and complexity to be found within the Jovian system.

A further example of this can be found with Io’s big brother, Ganymede. The third of the Galilean moons in terms of distance from Jupiter, Ganymede is not only the biggest of the Galilean moons orbiting Jupiter, it is the biggest and most massive natural satellite in the solar system. In fact, if it were orbiting the Sun rather than Jupiter, it would be classified as a planet, being even larger than Mercury.

Ganymede, like its smaller siblings around Jupiter – and the rocky planets of the inner solar system – is a complex place enjoying a complicated relationship with its parent; one which shares near-similarities with Earth’s relationship to the Sun.

Much has long been known about Ganymede as a result of observations made from Earth – such as via the Hubble Space Telescope – and by the various missions which have flown past or orbited Jupiter. These have helped us confirm that Ganymede has a sufficiently warm interior to support a global liquid water ocean beneath its crust, an ocean larger by volume than all of Earth’s combined.

We’ve also been able to (largely) confirm the presence of a tenuous atmosphere of oxygen and CO2, which seems to be particularly concentrated around the northern and southern latitudes, likely constrained by the interaction between Ganymede’s weak magnetic field and the far more powerful magnetic field generated by Jupiter – the predominant O2 content of the atmosphere is thought to be the result of water vapour escaping the moon’s interior being spilt by the radiation carried down over the poles by the magnetic field interaction.

It is this interaction between radiation, magnetic fields and the surface of Ganymede which have been part of the focus of a study made of the moon using instruments on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and which was recently published.

Ganymede’s surface is dominated by two types of terrain: bright, icy features with grooves, covering about two-thirds of Ganymede’s surface, and older, well-cratered and darker regions )on places scored by asteroid impacts of the moon’s more “recent” past, which could not be confused with the brighter terrain) . The two terrain types are not differentiated in terms of their location on Ganymede’s surface, they are instead intermingled, with the lighter terrain cutting swathes across the darker terrain.

Some of these brighter swathes – notably those around the Polar Regions – carry strong evidence of water ice, which appears to have been exposed by (in the words of the study) “the combination of micro-meteoroid gardening, excavating the ice, and ion irradiation”.

In other words, over the millennia, dust and material has been caught within the interactions between the two magnetic fields, smashing into the moon’s surface to expose the underlying water ice, allowing it to be irradiated by plasma also carried by the inflowing magnetic field, causing some of it to escape as water vapour which has been either further irradiated and broken down (thus giving rise to the accumulation of the tenuous, O2-rich atmosphere near the surface), or re-accreting as easily-identified water ice on the surface rock.

Whilst the two magnetic fields interact around Ganymede’s poles and along the moon’s “trailing edge” as it orbits Jupiter in a very similar manner to the interaction between Earth’s magnetic field and that of the Sun over our own poles, the spectral properties seen along the moon’s ”leading edge” in its orbit suggest that there is a far more complex, and yet to be understood interaction taking place between the magnetic fields of planet and satellite. Solving this mystery might require time – and some assistance in the form of the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission launched in April 2023, and due to reach the Jovian system in 2031, where it will likely uncover more surprises about both Ganymede and Europa.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: Jovian Moons, and lunar aspirations”