On October 11th, 2023, NASA revealed details of their first look at samples returned from asteroid 101955 Bennu, returned to Earth on September 24th by the OSIRIS-REx mission.

As I reported in Space Sunday: the return of OSIRIS-REx, the sample return capsule carried with it up to 250 grams of material from the carbonaceous asteroid – a lot more than had been anticipated, thanks to Bennu proving to be so brittle the sample mechanism smashed through its outer surface, clogging itself with material, rather than lightly “tapping, grabbing and departing”.

Following its recovery after landing in Utah, the capsule and containing the sample gathering head from the spacecraft was transferred to Johnson Space Centre and the Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science (ARES) centre (as I reported here), where for the last couple of weeks the sample container has been accessed and its contents subject to initial analysis.

It has still not been confirmed how much material has been obtained from Bennu; the opening of the sample canister revealed a fair amount of material was trapped between the lid of the canister and the membrane protecting the main bulk of the sample. This was painstakingly collected and formed the materials used for the initial analysis of the sample dust.

This initial analysis as revealed that – as expected, given it is a carbonaceous asteroid – the sample has within it evidence of both carbon and water, with the latter have a similar isotopic levels similar to those of Earth’s oceans. This was expected as it has long been the theory – supported by the examination of other asteroid samples returned to Earth by Japan’s Hayabusha and Hayabusha-2 missions – that C(arbonaceous)-type asteroids were responsible for bringing water and carbon to Earth early in its history.

Which is not to say that the samples do not offer a lot to learn; there is much that scientists do not know for certain about the Earth’s earliest history and its formation; much of what we do know is basis on hypotheses and scientific assumptions. The study of samples like those from Bennu samples could therefore allow many of those hypotheses to to more fully tested and the knowledge we lack or assume to be correct properly framed and understood.

Following extraction, the material from inside the sample container will be distributed to research centres in museums and universities around the world to enable a more extensive and as broad-ranging spectrum of independent analysis as possible over the coming months / years.

Psyche Launched

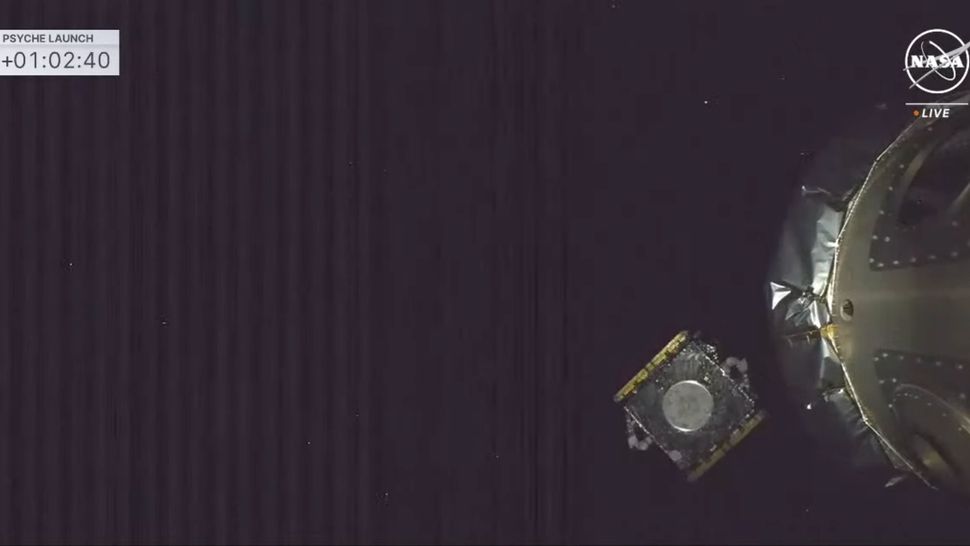

Following on from my previous Space Sunday article, and after being delayed almost 24 hours due to inclement weather, NASA’s mission to asteroid 16 Psyche got underway at 14:19 UTC on October 19th, 2023 when a Falcon Heavy lifted-off from Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Centre, Florida.

After a flawless launch the rocket – comprising a core Falcon 9 booster with two additional first stages of the same rocket acting as strap-on boosters – rose into a cloudy sky over Florida. Just over two minutes into the flight, the side boosters separated to complete a “burn back” manoeuvre allowing them to return to Florida to land at Cape Canaveral Space Force Base adjacent to Kennedy Space Centre a few seconds apart, the landings marking the 4th successful flight for both units.

The spacecraft separated from the upper stage of the booster around an hour after launch, having been delivered to an extended orbit around Earth. There then followed a further 30 minute period of silence as the vehicle powered-up and oriented its communications system to call home with its first batch of data, indicating all was well and establishing a firm link with mission control.

The next 100 days will see the spacecraft comprehensively checked-out in terms of its flight systems – notably the four Hall-effect SPT-140 ion thrusters. This will be used serially throughout the flight to propel the vehicle to its rendezvous with 16 Pysche and enable it to slow down for an orbital rendezvous.

This checkout will be completed over the next week or so, and prior the vehicle being ordered to use the thrusters to start pushing itself away from Earth and into a heliocentric orbit around the Sun to reach Mays in 2026. Once there, it will use the planet’s gravity to help swing itself onto an intercept with 16 Psyche, where it will arrive in the latter part of 2029 to commence its science operations over an initial 21-month period.

As I noted last time around, the journey to Mars will see NASA carry out a test of their Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) laser communications system, which could greatly increase the data rate and bandwidth of communications used with deep-space missions. The first test for DSOC should come in about three weeks from launch, when the vehicle will be 7.5 million kilometres from Earth. They will then be periodically repeated and extended as the spacecraft reaches a distance of to 2.5 AU from Earth.

The launch marked the eighth for what is now the world’s second most powerful launch vehicle currently regarded as operational (the most powerful title having been taken by NASA’s Space Launch System), and the 4th for 2023. However, it was particularly noteworthy for SpaceX, as it marks the first time NASA has used the rocket, and several concessions had to be made in order for this to go ahead.

The booster is also set to become a mainstay for several major NASA missions over the next few years. These comprise the launch of the 2.8 tonne GOES-U weather satellite and Europa Clipper mission to the Jovian system (both in 2024), the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope in 2026/7 and – perhaps critically for NASA’s human spaceflight operations, the joint launch of the first two sections of the Lunar Gateway Station in the form of the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) and the Habitat And Logistics Outpost (HALO), a launch currently targeted for November 2025.

In this, and in difference to the hype and questionable capabilities of the SpaceX Starship / Super Heavy system, Falcon Heavy is proving itself as reliable a launch vehicle as the rocket from which it has been formed.

In Brief

India Moving Towards Crewed Spaceflight with Test Mission

It’s all systems go with India’s space efforts. After the success of its Chandrayaan-3 lunar lander and rover and the launch of its Aditya-L1 solar observatory mission, the country’s space agency is making final preparations for the first sub-orbital launch of its Gaganyaan programme / space vehicle system.

Taken from the Sanskrit gagana (“celestial”) and yāna (“craft” or “vehicle”), Gaganyaan is intended to be India’s home-grown, crew-carrying space vehicle, designed to allow up to three people to orbit for up to seven days at a time. As I recently noted, the programme is due to carry out two uncrewed orbital test-flights in 2024, and a crewed flight in 2025, making India he fourth nation to independently launch and orbit citizens in space after Russia, the United States and China.

However, ahead of these, on October 21st, India will use a purpose-built single-stage rocket to launch an unpressurised, unscrewed version of the Gaganyaan vehicle in a high-altitude abort test, seen as one of the final steps required to clear the vehicle as being ready for orbital flights.

The October 21st test, designated TV-D1 is specifically aimed as testing the capsule escape and landing systems. It will commence as the launch vehicle passes through Mach 1.2, when the motors on the crew escape system (CES) fire to pull the capsule clear of the booster. Once separated from the booster, the capsule will drop clear of the CES rocket tower, allowing the drogue parachutes to deploy. These will stabilise the vehicle so that the main parachutes will deploy, and – assuming all goes well – the craft will splash down in the Bay of Bengal to be recovered by units from the Indian Navy.

Following the flight, both the capsule and its parachutes will be examined prior to a further test flight – TV-D2 – taking place, possibly before the end of the year. This will again be a sub-orbital lob, designed to test the overall flight parameters for the vehicle during an ascent to orbit. Providing TV-D2 is a success, the way will be clear for the first of the uncrewed orbital flight tests.

Fly the Labyrinth of Night

Mars is a world of the most amazing landscapes, from craters that were once home to lakes, the broad lowlands of the northern latitudes which once sat beneath a world-circling sea, the mighty highlands of the Tharsis Bulge with its great volcanoes, as it sits almost on the opposite side of the planet to the 2,300 km diameter impact basin of Hellas – the third largest impact crater in the solar system – and, of course, the great tear of the Vallis Marineris , the “Grand Canyon” of Mars, 5,00 km in length and in places almost matching the 7 km depth of Hellas Basin.

Sitting Between the Vallis Marineris and the Tharsis Bulge is the Noctis Labyrinthus (“the Labyrinth of Night”), a vast region of faults and graben forming a network of deep valleys and channels roughly the length of Italy. Believed to be the result of volcanic activity within the Tharsis uplands and surrounding the western end of the Vallis Marineris, it is a remarkable sight when seen in orbital pictures of Mars. Within it has been found evidence of a wide diversity of hydrated minerals which point to water having once been present in some quantity.

Noctis Labyrinthus is now the subject of a newly-released film from the European Space Agency. Comprising hundreds of individual high-resolution images of the region captured across multiple orbital passes by the Mars Express mission, which have been combined with terrain elevation data also recorded by the spacecraft, the film presents an idea of what it might be like to fly over Noctis Labyrinthus in a small aircraft. But rather than have me dribble on about it, watch the results below – and be sure to read the description accompanying it.

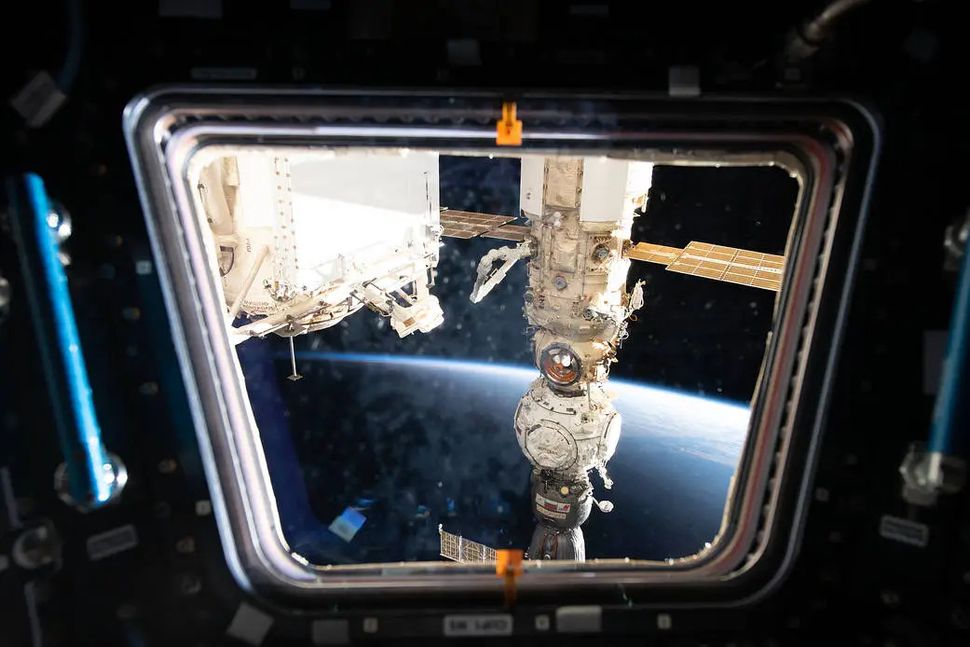

Russian ISS Module Experiences Leak

Russia has suffered another coolant leak – the third in 12 months –, once again losing ammonia from one of its orbital units. However, whereas the first two occurred with crewed spacecraft – first the Soyuz MS-22 vehicle, covered extensively in these pages (see here, here and here) and then just two months later by the Progress MS-21 resupply vehicles (see here), the latest was with a coolant system on one of the Russian modules of the International Space Station (ISS) itself.

That module is the Nauka Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM), the 13-metre pressurised module added to the ISS as the last-but one of the current permanent pressurised elements to be added to the station (only the 5-metre docking hub and storage area has been added since Nauka docked with the station), arriving at the station in July 2021. The leak occurred on October 9th within the secondary coolant system on the module, resulting in an outgassing of ammonia and the cancellation of a planned spacewalk in order to avoid the potential contamination of space suits whilst the leak was in progress.

Although Nauka is one of the most recent additions to the ISS, it is actually one of the oldest on the station in terms of its construction, elements having initially been fabricated in the late 1990s, with overall assembly dating back to the early 2000. It was originally scheduled for a 2007 launch, but this was repeatedly pushed back due to a series of repeated leaks and faults uncovered during testing, the module only being cleared for launch in 2020, when many of the components within the module were are the limits of their 20-year operating warranty. It also suffered a software glitch not long after arrival, causing the thrusters on the module to fire, pushing the station into an unexpected slow rotation. As ground controllers were unable to shut down the module’s thrusters, the motion had to be countered by firing the thrusters on the Zvezda module and then a Progress vehicle until Nauka exhausted its gas propellant reserves.

A cause for the leak has yet to be given, although the Russian space agency Roscosmos stated that it did not impair operations in the module, the primary cooling circuit being unaffected – an assessment with which NASA has agreed. Both of the leaks on the Soyuz / Progress vehicles were attributed by the Russian agency to micrometeoroid – tiny pieces of natural space or man-made debris – striking the exposed radiators of both vehicle’s cooling systems, an analysis NASA still does not share, even after studying data and evidence supplied by Roscosmos. As such, it will be interesting to see what is said about this latest leak.