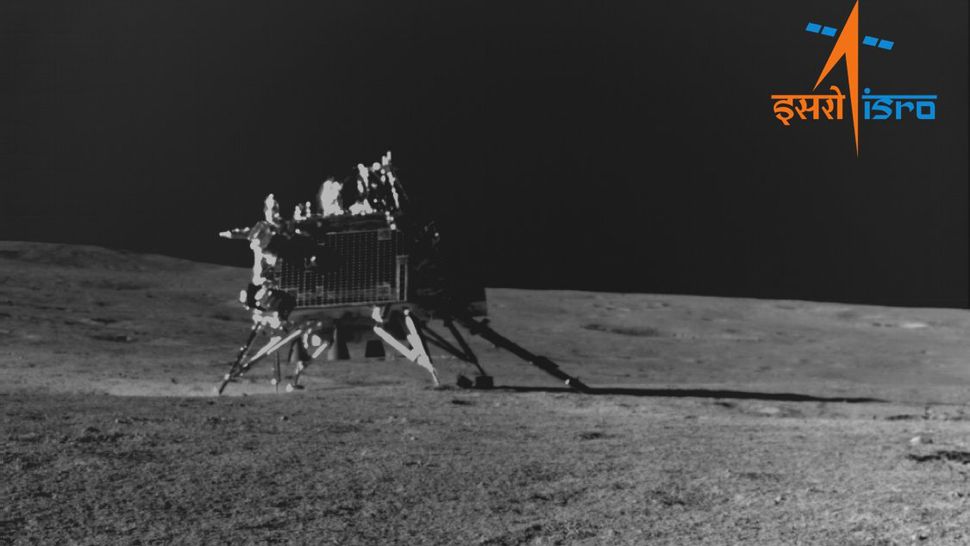

In my previous update, I noted that the Pragyan rover element of India’s Chandrayaan-3 lunar mission had been put to sleep in preparation for the onset of the long lunar night settling in, the little rover having completed its core mission. Within hours of that report being published, and again, a little ahead of schedule, the Vikram lander was commanded to place itself in hibernation in readiness for some 15 days without sunlight.

Again, the reason for this was simple: the lander had completed its entire primary mission, and controllers hoped that by allowing it time to fully charge its batteries ahead of the onset of the lunar night-time, it will have sufficient power to run its electrical circuits through until the Sun rises over the landing zone on around September 22nd, 2023.

Neither lander nor rover have any direct heating systems with which to keep themselves warm, and so both are reliant on the heat produced by the batteries being sufficient to keep their electrical circuits from freezing in temperatures which may get as low as -120oC, and that the batteries will last long enough so they can be recharged once sunlight does return.

Most impressively, shortly before the command to go into sleep mode was sent, Vikram was commanded to perform a short “hop” on September 2nd, using its landing motor to jump around half a metre, turning itself in the process so its solar array will more directly face the rising Sun.

The mission’s success and catapulted India’s growing space ambitions into the spotlight – the country is well along the road to gaining a human spaceflight capability thanks to the in-development Gaganyaan vehicle, capable of flying up to 3 people to orbit for up to 7 days. Currently, this project is targeting 2024 for two uncrewed test flights for the craft, to be followed by a crewed launch in 2025, which would make India the 4th nation to have an independent humans-to-orbit capability after Russia, the United States and China.

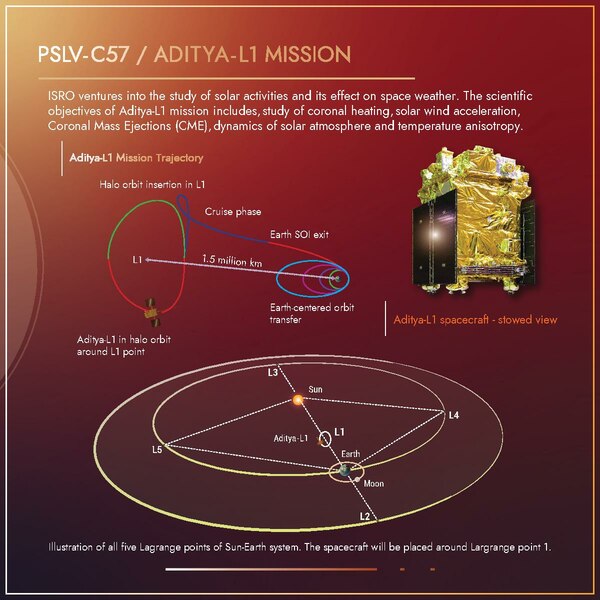

Meanwhile, and in terms of science missions, India has already followed Chandrayaan-3’s success with another ambitious mission: that of its first dedicated solar observatory, Aditya-L1 (“Aditya” being the Sanskrit for “Sun”).

Launched via India’s medium-lift Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SDSC), Sriharikota, at 06:20 UTC on September 2nd, the observatory separated from the launch vehicle around 63 minutes into the flight to start a 109-day journey to the Sun-Earth Lagrange L1 position, 1.5 million km from Earth, and lying between Earth and the Sun.

The first part of this comprised a series of polar orbits around the Earth carried out through until September 10th, which increased the vehicle’s apogee to move it further from Earth using minimum propellants. Two more such manoeuvres will take place during mid-September, allowing the observatory to transfer itself across to a halo orbit around the L1 position, which it should reach in early December 2023, and from where it can observe the Sun continuously.

The mission’s primary objectives are:

- Observation of the dynamics of the Sun’s chromosphere and corona. In particular, to engage in studies of chromospheric and coronal heating, examine the physics of partially ionised plasma, of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and their origins, and observe coronal magnetic field and heat transfer mechanisms, and flare exchanges.

- Observation of the physical particle environment of its immediate surroundings.

- Probe drivers for space weather, and the origin, composition and dynamics of solar wind.

A unique aspect of the telescope will be its ability to obtain near-simultaneous images of the different layers of the solar atmosphere, allowing scientists to observe how energy is channelled through it. This will allow scientists to make determinations about the sequence of processes in multiple layers below the corona that lead to solar eruptions. One of the mysteries of the Sun is that its upper atmosphere has a temperature of 1,000,000ºK, as opposed to just 6,000ºK at the Sun’s surface. As such, it is hoped that this kind of simultaneous observation of multiple layers of the Sun’s atmosphere will reveal a new understanding of solar dynamics and the interplay of solar weather and Earth which had thus far escaped understanding.

Japan Launches XRISM and SLIM

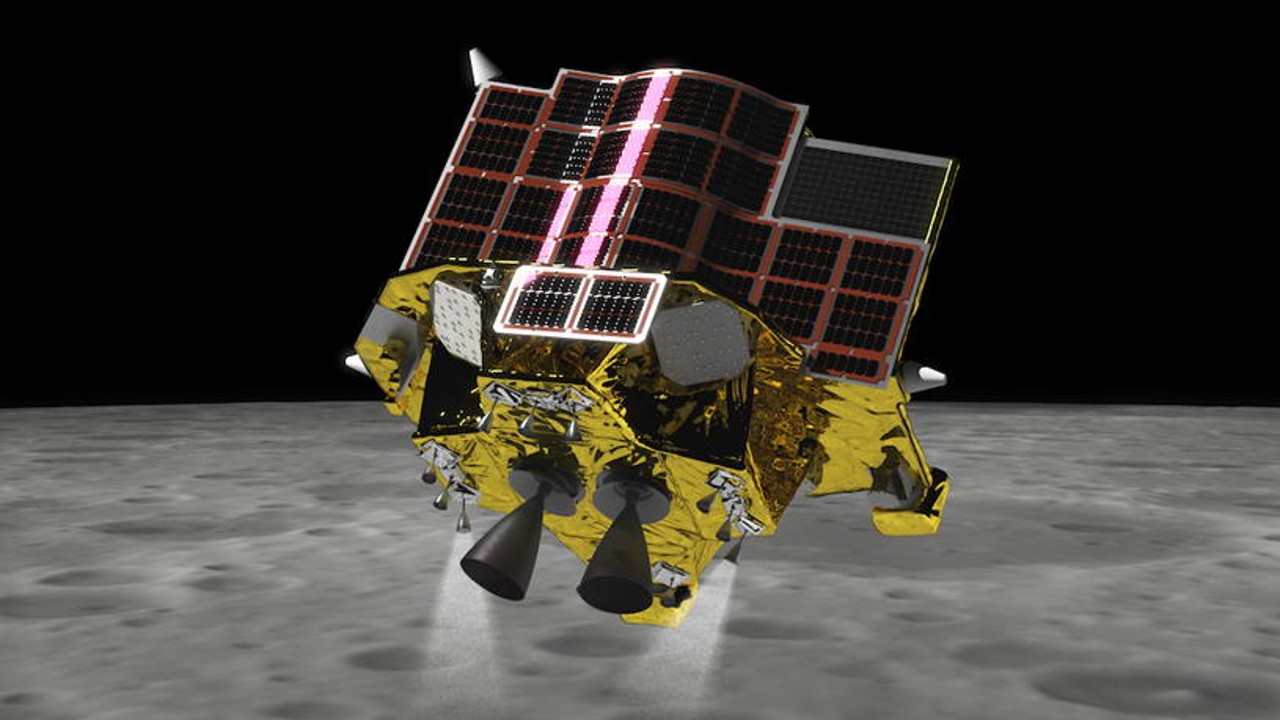

Although 10 days later than originally planned, Japan has launched its XRISM (pronounced “crism”) space observatory and SLIM Moon lander (also called “Sniper”), when a H-2A rocket lifted off from Tanegashima Space Centre at 23:42 UTC, and both craft deployed successfully less than an hours after the launch.

As I’ve previously reported, the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon, massing the 590 kg including its propellants, is Japan’s first attempt to land on the Moon. It is primarily a technology demonstrator, due to land within the relatively young (and small – just 270m across) Shioli impact crater, located just below the Moon’s equator, in 3 to 4 months time. Despite its tiny size, the lander is equipped with a suite of science instruments and will also deploy two palm-sized lunar rovers.

XRISM – the X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission – has a much closer destination than the Moon: an orbit just 550 km above the surface of Earth. Here, over an initial primary mission of 3 years, the 2.3 tonne telescope – defined officially as an “interim” observatory, which should not be taken to mean its role is unimportant – will attempt to provide breakthroughs in the study of structure and formation of the universe, outflows from galaxy nuclei, and dark matter.

A successor to Japan’s Hitomi X-Ray telescope, lost in March 2016, just a month after its launch in February 2016 thanks to an attitude control system failure, XRISM is also an international venture, involving both NASA and the European Space Agency. In particular, it will not only be a science instrument but also a technology demonstrator for ESA’s Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics (ATHENA) telescope, due to be launched in 2035.

XRISM carries two instruments for studying the soft X-ray energy range, Resolve and Xtend, each with its own telescope. Resolve is an X-ray micro calorimeter developed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, whilst Xtend is an X-ray CCD camera. Both will operate in concert with one another, with a combine focal length of 5.6 metres.

NASA’s SLS “Unsustainable”

The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued an audit report in which it notes that NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), the backbone of the American-led Artemis Project to return humans to the Moon, is at risk of becoming “unsustainable”.

With one successful flight under its belt – Artemis 1 – the project has thus far cost NASA US $11.2 billion since development commenced in 2011 (an amount which covered everything up to and including Artemis 1). A further US $11.2 billion has been requested by the White House to sustain SLS from 2024 through until the end of 2028, to allow NASA to further develop and enhance the system.

This is somewhat at odds with a 2022 announcement by NASA that it plans to develop a contract with Boeing and Northrop Grumman, the prime contractors for SLS and operating under the name Deep Space Transport, which the agency states will include up to 10 SLS launches while will over time reduce the production costs for those vehicles by up to 50%.

In their report, the GAO points out that the methodologies NASA uses to determine the costs associated with SLS are not easy to define. As, such, while there has been “some progress” in the agreement with Deep Space Transport, there is a real risk SLS costs will spiral, and suggests NASA starts to be more transparent in their SLS estimates and in how it manages expenditure.

NASA does not plan to measure production costs to monitor the affordability of the SLS programme. These ongoing production costs to support the SLS program for Artemis missions are not captured in a cost baseline, which limits transparency and efforts to monitor the program’s long-term affordability.

US GAO Audit, September 2023

In this regard, the GAO notes that while NASA has been forced to acknowledge the overall timeline for Artemis continues to slip for assorted reasons, costs associated with various missions have not been updated to reflect this. As such, whilst NASA has stated the cost of building the SLS vehicles to be used with Artemis 3 and 4, the reality is that the costs for these vehicles are actually increasing. As a result, an despite statements to the contrary by NASA, GAO believes SLS launches are liable to remain at around US $4.1 billion each rather than decreasing over time to around US $2 billion each.

The report is the latest of a string of GAO audits across almost a decade, all of which have critiqued NASA over a lack of proper baselining and transparency with regards to Artemis and SLS. At the time of writing, NASA had yet to respond.

SpaceX Starship Update

The Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) has issued the final version of a report into the failures of the first orbital launch attempt by SpaceX using their massive Starship / Super Heavy vehicle. The report, production of which was led by SpaceX, will not be made public due to “proprietary and export-controlled information”, identified “multiple root causes” for the failure of the Booster 7 / Starship 24 combination – none of which are to be made public either.

In a separate statement, SpaceX pointed to “propellant leaks” within the engine bay resulting in fires which severed connections with the primary computer system being a significant factor on the vehicle loss. Whilst in essence accurate, the statement totally avoids mention of the fact the leaks were most likely due to the force of the Super Heavy’s thrust excavating the unprotected concrete apron directly under the the launch mount, throwing significant amounts of concrete up to a kilometre from the launch site – and almost certainly into the engine bay to cause damage which may have resulted in at least dome of the leaks.

As many – myself included – noted, the April 20th flight was on questionable value even before it lifted-off. Since then SpaceX have sought to rectify the most glaring omission from the launch facility – a water deluge / sound suppression system (which has shown promise under a couple of short, partial-power tests, but which has yet to prove itself under the full thrust of a Super Heavy booster, and likely will not do so until the next launch).

In addition, there have been multiple changes to the flight software and systems, together with a wide range of physical updates to the vehicles, some of which pre-dated the April 20th launch attempt and rendered Booster 7 pretty much obsolete. How many of the modifications count towards the 63 “corrective actions” the FAA report states must be made before it will grant SpaceX a license for a further launch attempt, is unclear. Finally, and whilst unrelated to the launch failure, SpaceX have further altered the design to allow for “hot staging”: allowing Starship to ignite some of its engines prior to separation from the Booster, potentially increasing the payload-to-orbit capability.

And if it sounds odd that SpaceX led the investigation into the loss of its own vehicle, it is not. The FAA simply doesn’t have the breadth of expertise to complete such an investigation itself. Instead, it relies on input from a range of agencies as required – such as the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the US Air Force, the US Space Force, NASA, etc., and, in the case of a commercial launch provider – the provider and its contractors, as and where required.

Meanwhile, in a move which has SpaceX fans making assorted proclamations about an imminent further launch, the next vehicles designated to attempt to reach orbit – Booster 9 and Starship 25 – have been “stacked” on the repaired and updated launch mount. However, and in response to comments on such an “imminent” launch from fans (and Musk himself), the FAA has indicated that the original launch license was only for the April 20th launch – so SpaceX must show it has complied with the accident report and apply for a further license before it will be allowed to proceed.

A further twist to this is that the FAA is itself being sued by a number of environmental and other groups over the SpaceX site at Boca Chica. They claim that by allowing SpaceX to largely author the original Programmatic Environment Assessment (PEA) relating to SpaceX’s use of the site, combined with the April 20th failure, the FAA has materially failed to meet its obligations, and should therefore be ordered to carry out a full Environmental Impact Study (EIS) – a process which could take 2-3 years. Depending on when hearing on the case are held, it is possible the groups involved could seek an injunction on launches until the court rules in the matter of the EIS.