India has finally launched its third lunar exploration mission, Chandrayaan-3, after a series of delays pushed it back from a November 2020 target to August 2022 (thanks largely to the COVID pandemic), and then back to July 2023. Part of an ambitious programme initiated by the Indian Space Research Organisation to join in international efforts to explore the Moon (under the umbrella name of Chandrayaan – “Moon Craft” – initiated in 2003), the mission is also the result of an earlier failure within the Chandrayaan programme.

The first mission – Chandrayaan-1 – delivered a small orbiter to the Moon in 2008. It scored an immediate success for ISRO, when a lunar penetrator fired into the Moon’s surface by the orbiter confirmed the existence of water molecules trapped within the lunar sub-surface, whilst the orbiter did much to profile the nature of the Moon’s almost non-existent atmosphere.

In 2019, ISRO launched Chandrayaan-2, comprising an orbiter, a lander (Vikram, named after cosmic ray scientist Vikram Sarabhai, regarded as the founder of India’s space programme), and a small rover called Pragyan (“Wisdom”).

The orbiter is currently approaching the end of its fourth year of continuous lunar operations out of a planned 7.5-year primary mission. However, following a successful separation from the orbiter in September 2019, the Vikram lander deviated from its intended trajectory starting at 2.1 km altitude, eventually crashing onto the Moon’s surface, destroying itself and the rover, apparently the result of a software glitch.

Originally, that mission was to have been followed in 2025 by Chandrayaan-3, part of a joint mission with Japan and referred to as the Lunar Polar Exploration Mission. However, following the loss of the Chandrayaan-2 lander and rover – both of which were also testbeds for technologies to be used in 2025 -, ISRO decided to re-designate that project internally as Chandrayaan-4, and announce a new Chandrayaan-3 mission to replicate the lander / rover element of Chandrayaan-2 mission.

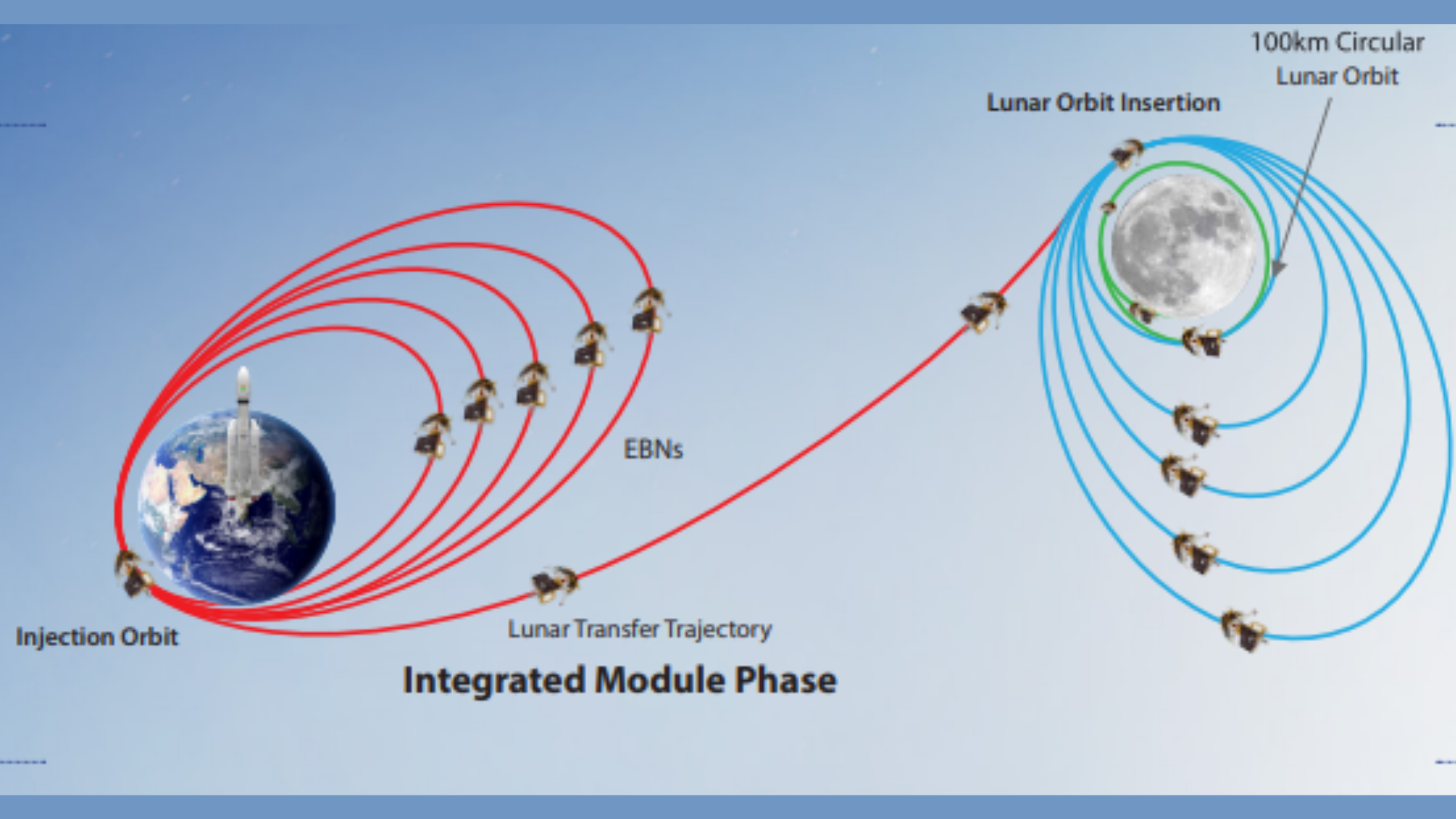

The revised Chandrayaan-3 mission lifted-off Satish Dhawan Space Centre at 09:05 UTC on July 14th, entering an elliptical orbit around Earth with a perigee of 173km and apogee of 41,762km. Over the next couple of weeks, the mission’s power and propulsion module will use 5 close approaches to Earth to further extend its orbit’s apogee further and further from Earth until it can slip into a trans-lunar injection flight and move to an initial extended orbit around the Moon around August 5th.

After this, the orbit will be reduced and circularised to just 100km above the Moon’s surface at this point, around August 23rd or 24th, 2023, the lander – also called Vikram, this time meaning “valour” – will separate from the propulsion module and attempt a soft landing within the Moon’s south polar region.

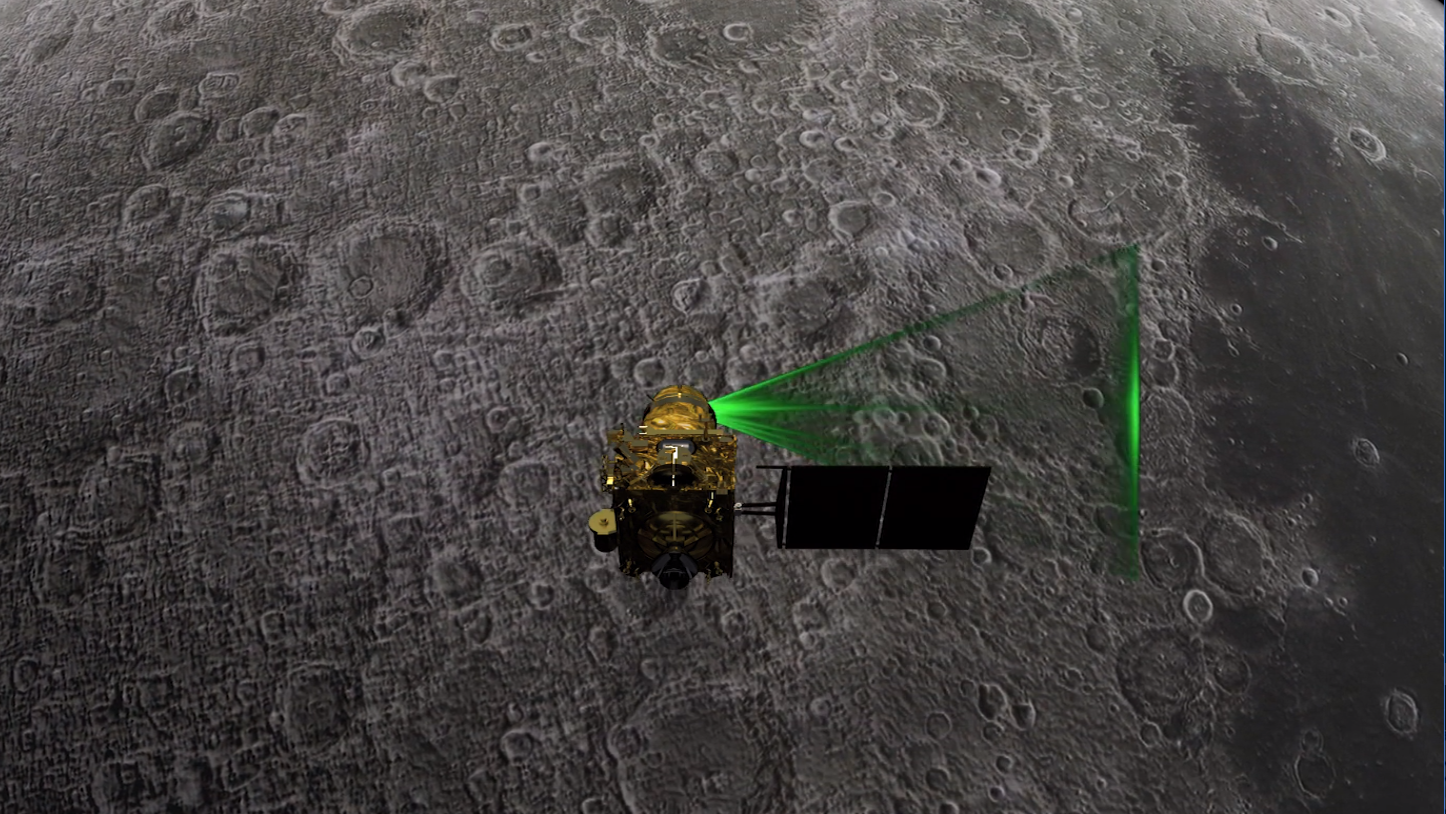

If successful, rover and lander will then commence a 15-day mission – the length of time sunlight will be available to power them before the onset of a month-long lunar night. The lander will conduct its work using three science instruments, and the 6-wheeled rover using two science payloads. These will be used to probe the composition of the lunar surface and attempt to detect the presence of water ice in the lunar soil and also examine the evolution of the Moon’s atmosphere. Communications with Earth will be maintained by both the orbiting propulsion module and the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter. If, for any reason, a landing on August 23rd or 24th cannot be achieved, the lander and rover will remain mated to the propulsion module through until mid-September, when the Sun will again deliver light (and power) to the landing area, allowing the landing attempt to be made.

How Old is the Universe?

It’s long been assumed that the universe is around 14 billion years old – or 13.7, according to a 2021 study using the Lambda-CDM concordance model. However, such estimates fail to account the likes of HD 140283, the so-called “Methuselah star”, which also estimated to be between 13.7 and 12 billion years old – as old as the universe itself, which in theory it should be a good deal younger.

This oddity has been further compounded by the James Webb Space Telescope locating numerous galaxies which appear to have reached full maturity – in cosmic terms – within 300 million years of the birth of the universe, rather than taking the billions evidenced by the vast majority of the galaxies we can see – including our own.

In an attempt to try to reconcile these oddities with our understanding of the age of the universe, a team led by Rajendra Gupta, adjunct professor of physics in the Faculty of Science at the University of Ottawa, has sought to develop an alternate model for the age of the universe – and appear to have revealed it could be twice its believed age.

They did this by combining a long-standing (and in-and-out of favour) theory called “tired light” with tweaked versions of certain long-established constants. “Tired light” suggests light spontaneously loses energy over time, and as it travels across the cosmos over billion years, it naturally red-shifts and so gives a false suggestion of cosmic expansion. It’s an idea which fell out of favour when other evidence confirmed cosmic expansion, but has regained so popularity since JWST started its observations; however, it doesn’t work on its own, so the researchers turned to various constants deemed to by immutable in terms of the state of the universe – the speed of light, the charge of an electron, and the gravitational constant.

By tweaking these, in a manner that is possible given our understanding of the universe, Gupta and his team found that it is possible to model a universe that appears younger than it actually is – in their estimation, 26.7 billion years of age. However, there is a problem with the idea: when you start tweaking known constants which cannot be proven to have changed, and it is potentially possible to come up with any model to fit an assumption. Ergo, the research cannot be seen as in any way definitive.

To counter this, Gupta points out there are a couple of hypothetical constants we use to account for the universe appearing and acting as it does – dark matter and dark energy. As I’ve noted previously, the latter is believed to be in part responsible for the expansion for the universe, and thus its age. However, its influence is currently hypothetical, and thus also subject to potential revision as such, the study suggests that if in influence of dark energy is found to be different to what is generally believed, it might yet indicate that the universe is a good deal older than is generally accepted.

Time will tell on this, but with ESA’s recently-launched Euclid mission is attempting to seek and characterise and potentially quantify both dark matter and dark energy, an answer might be coming sooner rather than later.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: the Moon, money and the universe”