Even as Europe’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) is commencing its long trek to the Jovian system in order to study Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa, three of Jupiter’s Galilean moons, more is being learned about Europa and its far more distant “cousin”, Enceladus, as the latter orbits Saturn.

In the case of Europa, the findings of a new study suggest that it may have formed somewhat differently than has long been thought, and that it may actually be less subject to deep heating and volcanism that has been thought – potentially decreasing the chances for it to harbour subsurface oceans and possible life.

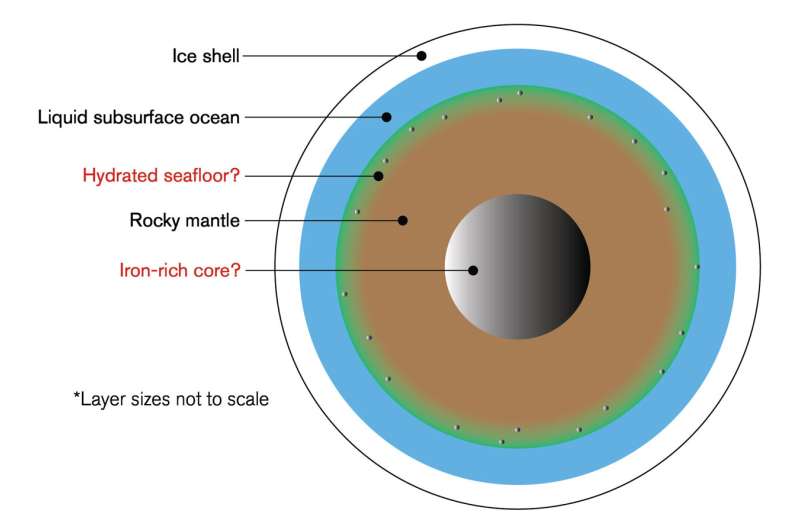

As has been mentioned numerous times in this column, Europa is of fascination because it is covered in an icy shell which appears to cover a liquid water ocean, churning over a rocky mantle and kept liquid due to a combination of internal heat radiating out from the Moon’s molten core and the gravitational “push/pull” inflicted on it by both Jupiter and other three Galilean moons, which give rise to heating through subsea volcanism and hydrothermal vents (which might also pump the ocean full of biologically useful molecules).

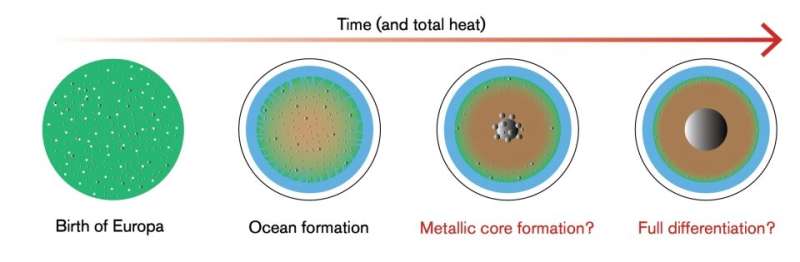

However, Kevin Trinh, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University (ASU), and his follow researchers suggest that Europa may have formed a lot slower than previously assumed, and somewhat differently to how it is generally assumed planets and small moons form, and that even now, it may not have a fully-formed core – possibly a result of its distance from the Sun.

The accepted theory for the formation of solid planets and moons is that as they coalesced out of ice, dirty, rocks, etc., and were compressed under increasing gravity – assisted by the Sun’s heat – underwent melting, the heavier filling into the centre of the planet / moon to form the core, with the “middleweight” rocks forming a semi-liquid, hot mantle, and the outermost becoming the brittle crust.

But given its size and distance from the Sun, Europa may never have reached the stage of the heaviest elements separating out of its mantle to for the core – or that it is still going through the process, but at a much slower rate and assisted by the gravitational flexing imposed on it by the other large Jovian moons and Jupiter itself.

This doesn’t mean the moon doesn’t have an ocean – Trinh and his colleagues believe the evidence for the ocean is too great to deny –, but rather its formation was different to previously thought, and may have been the result of a metamorphic process, which continues to power it today. In short, the rocks of the mantle were naturally hydrated (that is, contain water and oxygen), as the interior heat increased, it caused the water and oxygen to be released, forming the ocean and its icy shell.

For most worlds in the solar system we tend to think of their internal structure as being set shortly after they finish forming. This work is very exciting because it reframes Europa as a world whose interior has been slowly evolving over its whole lifetime. This opens doors for future research to understand how these changes might be observed in the Europa we see today.

– Carver Bierson, ASU’s School Of Earth and Space Exploration.

Just how far along the formation of a core might be, assuming this ASU study is correct, is an unknown. The study suggests that the core started to form billions of years after Europa’s formation, and that full differentiation has yet to occur.

If the theory is correct, it has some significant implications for Europa as a possible abode of life. As noted above, the traditional view is that the moon has had a hot, molten core which could, thanks to the gravitational flexing by Jupiter and the other large Jovian moons, power subsea volcanism and venting sufficient to create hotspots of life in the ocean depths. Without such a fully-formed core, however, it is unlikely that such is the case. But this does not mean that Europa is necessarily lifeless.

It could be that the heat within the rocky mantle – again driven by gravitational flexing – could lead to a more uniform heating of the sea floor, allowing for life to be more widespread around Europa and feeding on the minerals and chemicals released by the hydration process. However, the flipside to this is that such heating could equally leave much – if not all – of the ocean little more than an icy slush, either limiting any life to a very narrow band of heated water very close to the sea floor, or frozen out in the slush.

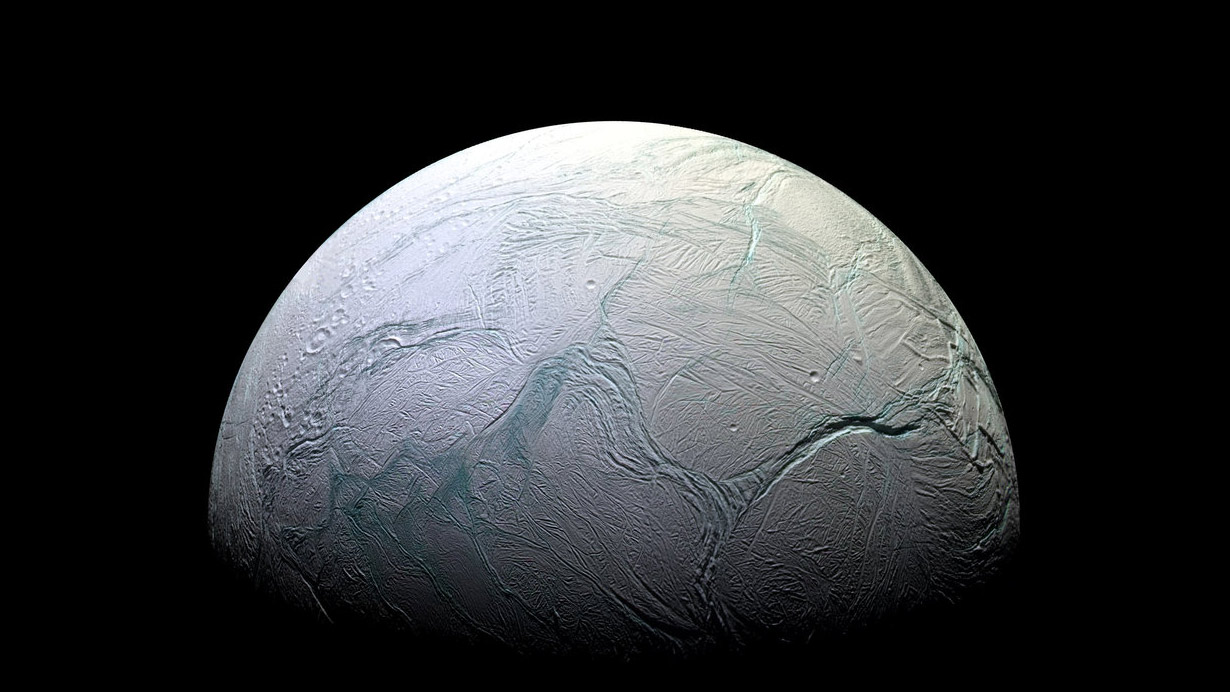

In the meantime, while Enceladus is even further from the Sun and a lot smaller than Europa – but the evidence for it having a subsurface ocean is more compelling. The southern polar area has long been subject to out gassing material into space – material which is known to be contributing to the growth of Saturn’s E-ring.

The out gassing was first imaged by NASA’s Voyager 2 vehicle in the 1980s and again by the joint European-NASA Cassini mission, which saw the Cassini spacecraft actually pass through some of the plume of material several times, confirming the presence of water vapour and other minerals, all of which are almost contributing to the tiny moon having a very tenuous atmosphere.

Data on the plumes gathered by Cassini have been the subject of extensive studies since they were gathered, revealing that do contain very simple organic molecules and even molecular hydrogen and silica. All of this indicates that chemical reactions between water and warm rock are occurring on the seafloor under Enceladus’ ocean, most likely around hydrothermal vents.

For the last 5 years, a team of scientists at Freie Universität Berlin, have been studying data from a number of sources – Cassini and Earth-based observations – relating to the materials found within Saturn’s E-ring, which, as noted, is at least in part made up of material ejected from Enceladus in an attempt to both better understand the composition of the ring and its relationship with material coming from the moon. What they’ve found has come as a surprise to many planetary scientists: phosphorus.

The importance here is that phosphorus is the rarest of six elements which life here on Earth utilises in various forms – such as combining it with sugars to form a skeleton to DNA molecules and also helps repair and maintain cell membranes. What’s more, the concentrations of the mineral within the plumes are about 500 times greater than the highest known concentrations in Earth’s oceans. While the phosphorus has been detected within Saturn’s E-ring rather than within the plumes rising from Enceladus, its discovery nevertheless is seen as offering “the strictest requirement of habitability” within the moon’s ocean, given that Enceladus is blasting material into the E-ring at the rate of 360 litres per second.

A 2018 study involving Enceladus’s ocean and the likely minerals in might contain had drawn the conclusion that any phosphorus concentrations on the moon would have been depleted in the moon’s oceans a long time ago, and thus unavailable for potential life. However, in reviewing the new findings, the team behind the 2018 study have stated their findings have now been overturned.

In particular, the Freie team also identified the presence of orthophosphate within the phosphates of the E-ring. This is the only form of phosphorus that living organisms can absorb and use as a source of growth. This suggests that not only are phosphates “readily available” in Enceladus’ oceans, it is in forms simple life can make use off to help in its development. Coupled with the fact that the oceans of Enceladus are likely warm and rich in a broad range of minerals and chemical elements, further raises the potential for the moon to harbour microbial life. This had already led to renewed calls for a dedicated mission to the little moon for a more direct investigation.

“What Difference a Day Makes, 19 Little Hours”¹

How long is a day on Earth? 24 hours or thereabouts? Well yes, that’s pretty much the case – and has been throughout human history. But that doesn’t mean it has always been the case.

The standing theory has long been that following their formation, Earth and Moon were a lot closer together, with the latter orbiting the former in a lot less than the 27-28 days we’re familiar with today, and the Earth itself spinning a lot faster about its axis. However, over time, the Moon’s distance from Earth slowly increased, leading to longer and longer orbital periods whilst also reducing Earth’s rotational spin as a result. These changes have been assessed by geologists through the study of ancient sedimentary rocks that contains preserved layers from tidal mud flats. By counting the number of sedimentary layers within these rocks caused by tidal fluctuations, they could determine the number of hours per day during previous geological periods.

However, such rocks are exceptionally rare, and our ability to collect enough limited, such that it has been impossible to build up a complete picture of exactly how the length of day here on Earth has changed, and when, leading to the assumption that the change has been more-or-less constant over time, with the Moon continuing to move away from Earth, and the Earth continuing to gradually slow in its rotational period.

However, there is another method for estimating day length. It is called Cyclostratigraphy, and it involves the study of astronomically forced climate cycles or variations in Earth’s orbit around the Sun due to interactions with other masses within the solar system. Called Milankovitch cycles, they track how solar irradiation has varied over time across the Earth’s hemispheres, influencing both the climate and the deposition of sedimentary rocks.

It is these cycles which have been the focus of a study conducted in China by Ross N. Mitchell, a Professor of geosciences at the CAS State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics and the College of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Uwe Kirscher, formerly a professor at the University of Tübingen, Germany, prior to relocating to Australia to further their research, where he is now a Research Fellow at The Institute for Geoscience Research at Curtin University. Their work – which is undergoing peer review – has resulted in some usual findings.

Most significantly, it is that the shifting length of the terrestrial day has not been constant – there have been periods in which it remained the same length for a period of time, before once again growing longer, and then pausing again. In particular, they found that for around a quarter of the Earth’s lifespan, covering a period between two billion and one billion years ago, the length of day remained roughly 19 hours long after a period of slow lengthening, before resuming its slow increase to the roughly 24 hours we’re familiar with in our “modern” geologic era.

Exactly what caused this particular pause is not entirely clear; Mitchell and Kirscher posit that a major contributing force was what the call an “equilibrium” between the “wobble” evident in the Earth’s spin and its axial tilt. This, combined with the growing influence of the Moon on Earth’s tides as the planet’s spin slowed, together with the changing influence of the solar wind on heating Earth’s increasingly dense atmosphere, resulted in the length of day become stable at 19 hours.

What is particularly intriguing about the study, is that the stabilising of the length of day occurred between the two largest rises in oxygen content in our atmosphere – the Great Oxidation Event, where photosynthetic bacteria dramatically increased the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere, and the Cryogenian period, which included the Marinoan glaciation period when the entire surface (or close to it) was covered in ice. So, if confirmed, the study’s findings will indicate that the evolution of Earth’s rotation is most more closely related to the composition of its atmosphere and the rise of life as we know it than may have been previously realised.

However, it is the overturning of the accepted theory that it was the Moon which gradually absorbed Earth’s rotational energy, slowing the planet down whilst it down whilst boosting itself into a more distant orbit, which is liable to have the widest implications for planetary scientists as they seek to understand the processes at work in bringing about the Earth-Moon system has we know it today.

Humans Appear to be Affecting Earth’s Axial Tilt

In news which is liable to have climate change deniers barking, disclaiming and attempting to deride, a new study suggests that humans are influencing the Earth’s rotational poles, and adding a further factor on our impact on climate change. This is the axis around which the planet spins and denoted by two imaginary poles extending from the northern and south hemisphere, referred to as a rotational poles, and which are not the same as the north and south poles.

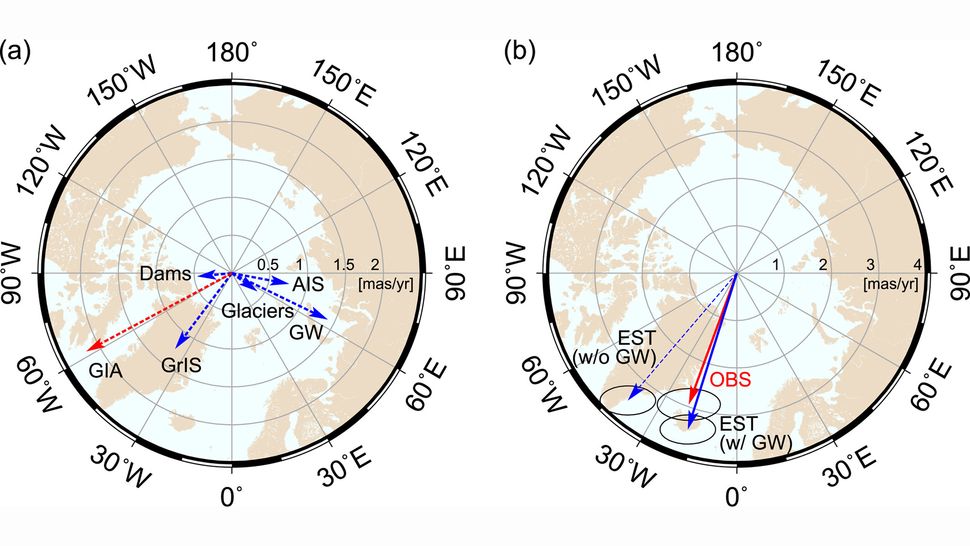

The rotational poles have long been known to change over time – generally by a few metres every few years, wobbling back and forth, and this has been recognised as feeding into some of the unpredictability of seasonal weather in the northern and southern hemispheres. However, the shift in the rotational poles is something that can be mapped – something a team of researchers at Seoul National University, Korea have been doing.

Using polar motion data which has been gathered since the late 1800s and right through the 20th century to current times, the team attempted to build a model to help in the role axial tilt might play in climate change alongside man-made influences. However, in testing the model using data gathered up until the early 1990s and then comparing it with actual tracking of the moment of the rotational poles through to 2016, the team found their model was, year-on-year, becoming increasingly inaccurate, to the point where by 2016, the model was under-estimating the degree of change by 78.5 cm – over 3/4s of a metre when compared to known data gathered through Earth observation satellites. The problem was – why?

As one of the aims of the study was also to assess the global distribution of subsurface reserves of water, the Seoul team looked at the global use of groundwater for the same period (1993-2016), They found that in that time, the extraction of freshwater reserves from within the planet increased year-on-year, particularly from mid-latitudes where warmer and warmer seasons were being experienced. When the mass of this water was calculated and its distribution taken into consideration and fed into the computer model for the shifts in Earth’s rotational tilt, the figures corrected by – wait for it – 78.5 cm, to match the observed positions of the rotational poles once more.

While a single study is too limited to draw absolute conclusions, the implications of the Seoul study do suggest a correlation between increasing use of groundwater reserves by humans, and its impact on the movement of the rotational poles, and this shift feeds back into seasonal climate changes, potentially adding another human factors involved in global climate change.

- With apologies to Stanley Adams, Maria Grever and Aretha Franklin.