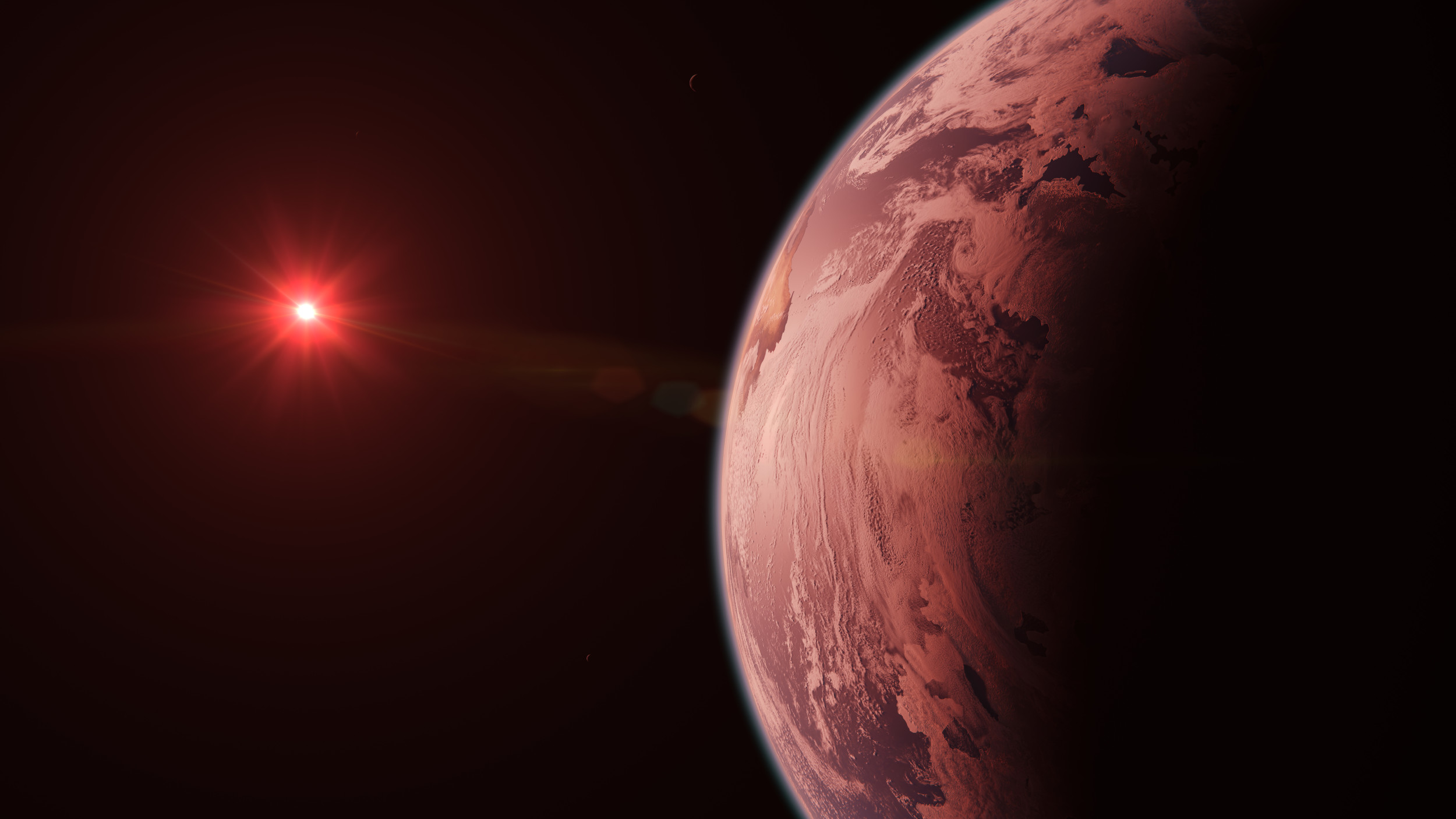

Scientists have once again been turning their attention to the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system – this time to try to find evidence of technosignatures – artificial radio transmissions if you will – emanating from the system.

TRAPPIST-1 is a red dwarf star some 40 light years from Earth which had been previously known by the less exotic designation 2MASS J23062928-0502285. The name change came about in 2017, after extensive observations led by the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) system revealed the star had no fewer than seven roughly Earth-sized planets orbiting it (see: Space update special: the 7-exoplanet system). The discoveries marked the star as a prime contender for the study of exoplanet systems, not only because of its proximity to our own Sun or the number of planets orbiting the star, but also because three of the seven planets lay within the star’s “Goldilocks zone” – the region where everything is kind-of “just right” for liquid water to exist and – perhaps – life to potentially take hold.

However, there have always been caveats around any idea of any of the planets harbouring liquid water, much less life, the most obvious being whether or not they have an atmosphere. One problem is that red dwarf stars tend to be rather violent little fellows in comparison to their size, prone to extreme solar events which could, over time, simply rip away the atmospheres of any planets orbiting. Another, more intrinsic problem is that a new study suggests that it might be harder to confirm whether or not the TRAPPIST-1 planets have any atmospheres because the means by which scientists have generally used to try and identified whether or not tidally locked exoplanets might have atmospheres could well be flawed – of which more in a moment.

The issue of TRAPPIST-1 ripping away an atmospheres its planets may have had is a mixed one: on the one side, all of the planets orbit their parent star very closely, with orbits completed in periods measure from just 2.4 terrestrial days to 18.9 terrestrial days; this puts them well inside the “zone of violence” for any stellar outbursts from the star. On the other, TRAPPIST-1 is old: estimates put it at around 7.6 billion years old, or more that 1.5 times the age of our Sun, and it might be a much as 10 billion years old. This age means that as red stars go, it is actually quite staid, and may have passed through it more violent phase of life sufficiently long ago for the atmosphere of the more distant planets orbiting it, including those in the habitable zone where life may be able to arise, to have survived and stabilised.

One of the most interesting aspects of the TRAPPIST-1 system is that, even though they are tidally locked, two of the planets within the star’s habitable zone TRAPPIST-1e and TRAPPIST-1f – could actually have relatively benign surface temperatures on their surfaces directly under the light of their star, with TRAPPIST-1e having temperatures reasonable close to mean daytime surface temperatures here on Earth and TRAPPIST-1f matching average daytime temperatures on Mars. Thus, if they do have dense enough atmospheres, both could potentially have liquid water oceans constantly warmed by their sun, and the regions in which those oceans exist could experience relatively temperate weather and climate conditions.

Since the discovery of the seven planets, there have been numerous studies into their potential to harbour atmospheres and much speculation about whether or not they might harbour life. However, the idea that any life on them might have reached a point of technological sophistication such that we might be able to detect it is – if we’re being honest – so remote as to be unlikely simply because of the many “ifs” surrounding it. However, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to find out; for one thing, there is the intriguing fact that if any civilisation has arisen to a level of technology similar to ours on any of the planets, the relative proximity of the entire system means that it might have made the jump between them and achieved something of a multi-planet status.

Again, the chances of this being the case are really remote – but if it has happened, then there would likely be communications passing back and further the planets. Assuming that such communications are made via artificially modulated radio frequencies, we might be able to detect them from Earth. At least, this has been the thinking of a team of radio astronomers, and they’ve been putting the idea to the test using a natural phenomenon called planet-planet occultation (PPO). A PPO is when one planet comes between two others – in this case one of the TRAPPIST-1 planets and Earth.

The theory is that if the two alien words are communicating one to the other, then during a PPO, any radio signals from the planet furthest from Earth (planet “b” in the illustration below) direct at the occulting planet (planet “c”), would “spill over” their destination and eventually pass Earth, allowing us to detect them. Note this doe not mean picking up the communications themselves for any form of “translation” (not that that would be possible), but rather detecting evidence of artificially modulated radio frequencies that might indicate intelligent intent behind them.

To this end, a team of radio astronomers the latter’s Allen Telescope Array (ATA), originally set-up by the SETI Institute and the University of California, Berkeley, to listen to the TRAPPIST-1 system and gathered some 28 hours of data across several potential PPO events involving different planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system. In doing so, they collected some 11,000 candidate signals coming from the general proximity of the TRAPPIST-1 system. These event were then further filtered down using computer modelling to some 2,000 potential signals that could be directly associated with 7 PPO events. These 2,000 signals were then analysed to determine if any were statistically unusual enough to suggest they might be of artificial origin – that is, potential radio transmission.

Sadly, the answer to this was “no”, which might sound like a lot of work for no result; but just imagine if the reverse had been true; further, now the concept of using PPO events in this manner has been tested, it lends itself for potential use with other multi-planet systems orbiting relatively nearby stars.

The Problem of Atmospheres

Now, to circle back to the question of atmospheres on tidally locked planets. As noted above, such planets always have one side permanently facing their parent star and the other always pointing away into space, as the rotation of the planet is precisely in sync with its orbital motion around the parent star. This means that – again as already noted – if there is any atmosphere on such a planet, it might result in some extremes of weather, particularly along the terminator between the two sides of the planet.

However, if the atmosphere is dense enough, then conditions on the planet might not only be capable of supporting liquid water, they might also result in stable atmospheric conditions, with less extreme shifts in climate between the two sides of the planet, and while the weather would still be strange, it would not necessarily be particularly violent; thus, such planets might be far more hospitable to life than might have once been thought. And herein lays a problem.

To explain: exoplanet atmospheres are next to impossible to directly observed from Earth or even from the likes of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Instead, astronomers attempt to observe the spectra of an exoplanet, as this reveals the chemical composition of any atmosphere that might be surrounding it. But tidally-locked planets tend to be orbiting so close to their parent star that trying to obtain any atmospheric spectra is hard due to the interference of the star itself. Instead, a different technique is used.

As a tidally locked planet passes between Earth and its parent star it presents its dark side directly to us, allowing astronomers by dint of knowing the nature of the star itself, to calculate the temperature of the planet’s dark side. Then, as it moves around to the far side of the star relative to Earth, we get to measure its “light” side. Again, as the nature of the star and its light / temperature are “known”, it is possible to extrapolate out the likely temperature of the “light” side of the planet. With this done, the two temperatures can be compared, and if they are massively different, then – according to the thinking to date – viola! The planet has no atmosphere; but if the difference between the two is not drastically different, than it’s likely the planet has a nice, dense atmosphere.

Except a new study currently awaiting peer review points out a slight wrinkle in this approach. In it, researchers show that yes, while a dense atmosphere on a tidally-locked exoplanet would moderate the planet’s global temperatures and thus remove extremes, it could also result in the formation of upper atmosphere clouds across much of the dark side of the planet. Such clouds would have two outcomes: on the one hand, they would help retain heat within the atmosphere under them, keeping it much warmer than would otherwise be the case and making the entire planet potentially far more hospitable to life. On the other, they would “reflect” the coldness of the upper atmosphere such that when we attempt to measure the temperature of the planet’s dark side, we are actually measuring the temperature of the cold upper layers of the clouds, not the temperature of the atmosphere below them. This would result in the dark side temperatures appearing to be far lower than is actually the case, leading to the incorrect conclusion that the planet lack any atmosphere when this is not the case.

What’s the impact of this? Well, allowing for the study to pass peer review – and the author’s note that more work in the area is required, it could mean that we have dismissed numerous smaller, solid exoplanets as being unsuitable for life because “they have no atmosphere” when in fact they could in fact do so. Thus, there might be more potentially life-supporting planets than previously considered.